the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Film and the Arts

Quartetto di Cremona Perform in NYC

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Friday, 27 October 2023 18:02

- Written by Jack Angstreich

Photo by Pete Checchia.

At Weill Recital Hall, on the evening of Thursday, October 26th, I had the exceptional pleasure to attend an astonishing concert featuring the extraordinary Quartetto di Cremona, the members of which include violinists Cristiano Gualco and Paolo Andreoli, violist Simone Gramaglia and cellist Giovanni Scaglione.

The program began marvelously with a sterling account of Hugo Wolf’s wonderful Italian Serenade, his most famous piece outside the genre of the lied. Even more remarkable was a stunning rendition of Maurice Ravel’s glorious String Quartet—one of the supreme masterpieces of the form—the shimmering textures of which strongly recall the composer’s orchestral works. The initial Allegro moderato has a surprising intensity becoming more lyrical in passages and ending quietly, followed by an especially bewitching, briskly paced and energetic movement—markedAssez vif—with evocative, impressionistic sonorities. The subdued, reflective slow movement that succeeds it is solemn and more unconventional in structure while the dynamicfinaleis the most turbulent of the movements.

The second half of the event—devoted to a magisterial performance of Ludwig van Beethoven’s awesome, ambitious String Quartet in A Minor, Op. 132—was maybe equally memorable. Much of the opening Allegro is highly charged music although it is interlaced with that of a lighter, more graceful character, preceding an Allegro ma non tanto that is more cheerful, almost Mozartean, but with some intimations of greater seriousness. The weighty, exalting, slow movement—with a tempo of Molto adagio—has a religious gravity but with interpolations of melodious, quasi-Baroque episodes. The fourth movement—Alla marcia, assai vivace—is spirited and charming with contrasting interludes of an almost tragic cast while the exhilarating finale—marked Allegro appassionato—is exultant. An enthusiastic ovation was rewarded with an amazing encore: the incomparable First Counterpoint from Johann Sebastian Bach’s final work,The Art of the Fugue.

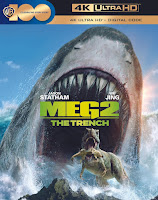

October '23 Digital Week III

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Thursday, 26 October 2023 02:55

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Emerson String Quartet Give Farewelll Performance at Lincoln Center

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 25 October 2023 13:31

- Written by Jack Angstreich

Emerson String Quartet receive standing ovation. Photo by Da Ping Luo.

At Alice Tully Hall, on the evening of Sunday, October 22nd, I had the exceptional privilege to attend the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center’s excellent farewell performance of the celebrated Emerson String Quartet. The members of the ensemble were violinists Eugene Drucker and Philip Setzer, violist Lawrence Dutton and cellist Paul Watkins.

The first half of the program was devoted to an accomplished account of the remarkable String Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, of Ludwig van Beethoven, presented here in its original version. The initial movement has a somewhat solemn, brief introduction marked Adagio, ma non troppo, with the main body an Allegro with more vivacious, brisk passages organized in a highly unconventional structure. The ensuing, short Presto is propulsive and ebullient and is followed by a slower movement—with a tempo of Andante con moto, ma non troppo—that is elegant, charming, graceful, even Haydnesque. The exquisite Alla danza tedesca movement that succeeds it—with an Allegro assai marking—is also delicate. The contrasting Cavatina—an Adagio molto espressivo—is ruminative, but not without lyricism—with a middle section that achieves an even greater intensity—and ends quietly. The astonishing, avant-garde, unusually ambitious finale—the famous, even infamous Grosse fuge, which the composer also published as an independent work—is agitated but gripping.

After intermission, the ensemble received the CMS Award for Extraordinary Service to Chamber Music in a modest ceremony. The second half of the concert was maybe even more memorable, consisting of an admirable rendition of Franz Schubert’s sterling String Quintet in C major, D. 956, which also featured cellist David Finckel, an original member of the group who left it in 2013. The opening Allegro ma non troppo movement is animated, melodious, and cheerful but not without darker undercurrents and more dramatic episodes, preceding an ethereal and enchanting Adagio with a tempestuous interlude. The marvelous, familiar Scherzo, marked Presto, is energetic and exhilarating, with a slower, more serious and inward Andante sostenuto Trio, and the finale, marked Allegretto, is dancelike and lively although with more pensive moments.

The artists received a very enthusiastic standing ovation.

The next Chamber Music Society program is on the evening of Sunday, October 29th, centered upon the great Russian composer, Sergei Rachmaninoff.

A Double Concerto With the NY Philharmonic

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Tuesday, 24 October 2023 14:31

- Written by Jack Angstreich

David Robertson conducts New York Philharmonic, photo by Brandon Patoc

At Lincoln Center’s David Geffen Hall on the evening of Saturday, October 21st, I had the pleasure of attending a terrific concert—which was notable for showcasing rarely encountered repertory—presented by the excellent New York Philharmonic under the superb direction of the irrepressible guest conductor, David Robertson.

The program began wonderfully with a masterly account of György Ligeti’s enchanting Mifiso la sodo (Cheerful Music) from 1948—a creation not without its eccentricities, nor lacking in ironic or satirical inflections—played in these concerts in its long overdue U.S. premiere and celebrating the centenary of the composer’s birth. Also remarkable was the brilliant realization of another work—too seldom heard—by the same author, the extraordinary Romanian Concerto of 1951. Neither piece strongly suggested the radical avant-gardism that would later become the famous hallmark of Ligeti’s mature style. About his discovery of the unusual instrument, the alphorn, that he employed to striking effect in this composition, he said:

The alpenhorn (called a bucium in Romanian) sounded completely different from “normal” music. Today I know that this stems from the fact that the alpenhorn produces only the notes of its natural harmonic series and that the fifth and seventh harmonies (i.e., the major third and minor seventh) seem “out of tune” because they sound lower than on the piano, for example. But it is this sense of “wrongness” that is in fact what is “right” about the instrument, as it represents the specific “charm” of the horn timbre.

On the Concerto itself, he commented:

In 1949, when I was 26, I learned how to transcribe folk songs from wax cylinders at the Folklore Institute in Bucharest. Many of these melodies stuck in my memory and led in 1951 to the composition of my Romanian Concerto [Concert Românesc].However, not everything in it is genuinely Romanian as I also invented elements in the spirit of the village bands. I was later able to hear the piece at an orchestral rehearsal in Budapest — a public performance had been forbidden. Under Stalin’s dictatorship,even folk music was allowed only in a “politically correct” form, in other words, if forced into a straitjacket of the norms of socialist realism. Major-minor harmonizations à la Dunayevsky were welcome and even modal orientalisms in the style of Khachaturian were still permitted, but Stravinsky was excommunicated. The peculiar way in which village bands harmonized their music, often full of dissonances and “against the grain,” was regarded as incorrect. In the fourth movement of my Romanian Concerto there is a passage in which an F-sharp is heard in the context of F major. This was reason enough for the apparatchiks responsible for the arts to ban the entire piece.

The opening Andante movement creates an impression of pensiveness while the ensuing Allegro vivace, which introduces a strong folk element,is—not unexpectedly—more exuberant. Contrastingly, the Adagio ma non troppo movement that follows is meditative and uncanny, recalling the music of Béla Bartók, and the finale, marked Molto vivace, is propulsive and dance-like with the folk melodies even more pronounced.

The renowned soloist, Yefim Bronfman, then entered the stage to confidently perform—these programs represent its New York premiere—the powerful Piano Concerto—of which he is the dedicatee—of contemporary Russian composer, Elena Firsova—which is notable particularly for its impressive orchestration. While oddly compelling, this advanced music is beyond my current ability to truly evaluate and resists description; the author of the work, who was present and afterwards joined the artists to receive the audience’s acclaim, has provided an interesting note on it:

The music of my Double Concerto for violin and cello, from 2017, was very personal and reflected my meditations about the mystery and meaning of Death. You possibly know a relevant quote from Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak: “Art is constantly preoccupied with two things: It always meditates about Death and in this way inevitably creates Life.” The introduction and both movements of the Double Concerto were based on the motif of Beethoven’s final movement of his String Quartet, Op. 135, “Muss es sein?” Only in the beginning I use the motif in its retrograde form and later, of course, in inverted form.

I mention this because my Piano Concerto in a certain sense is a kind of a twin composition with my Double Concerto. The music material of all three movements is based on the same motif. I did it absolutely unconsciously in the beginning, realised it only when I finished the first movement and was astonished how different the music is from the Double Concerto!

I would say only that in the Piano Concerto I concentrated more on the problems and questions of Life, but at the end everything is inevitably coming to the clock which reminds us that everything has its end. As in the Double Concerto, the last movement of the Piano Concerto is the main and longest part of the music.

The initial Andante seems haunted and agonized, preceding anAllegrothat has a similarethosbut is more energetic and intensely dramatic, with afinalethat is quieter and more serene for much of its length, but with very fraught, intensely dramatic passages, although concluding softly and mysteriously.

The second half of the event was at least equally memorable, consisting of a superlative—indeed seemingly perfect—rendition of the too infrequently presented, astonishing, unexpectedly ambitious early masterpiece of Johannes Brahms, the Serenade No. 1 in D major for Large Orchestra, one of the composer’s most Mozartean accomplishments and crucial to understanding his development as a major symphonist. The unusually joyous—for the composer—initial Allegro molto movement has a strongly pastoral quality that evokes the Symphony No. 6 of Ludwig van Beethoven while nonetheless remaining thoroughly Brahmsian in character. The transition to the leisurely, cheerful succeeding Scherzo—marked Allegro non troppo—is barely perceptible while theAdagio non troppothat follows is more inward and highly lyrical, but not tragic. The fourth, Menuetto movement possesses an unusual levity for the composer and theAllegrothat appears after it recapitulates the spirit of the first two movements. Also ebullient is theRondo,with the same tempo marking, that serves as a most dynamicfinale.

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up