the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Reviews

December '19 Digital Week II

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Tuesday, 10 December 2019 21:59

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Blu-rays of the Week

It Chapter Two

(Warner Bros)

Although as overlong as the first film and bloated with relentless and often redundant flashbacks, Andy Muschietti’s follow-up is more engaging, mainly because the lead actors, from Jessica Chastain, James McAvoy and Bill Hader to Sophia Lillis, Jaeden Martell and Finn Wolfhard as their younger selves, dramatize Stephen King’s juvenile material with no-nonsense professionalism.

There’s still the ridiculous, inane finale as the clown Pennywise morphs into other murderous creatures, but that’s to be expected from the rarely subtle King. The hi-def transfer is impressive; extras include a two-part making-of doc, featurettes and Muschietti’s commentary.

An Elephant Sitting Still

(KimStim)

The story behind Chinese director Hu Bo’s first (and only) feature is as saddening as his nearly four-hour, slow-burning drama about several downcast and defeated characters in modern-day China.

After finishing the film, Hu Bo committed suicide at age 29, leaving behind the question of what-could-have-been for a talented filmmaker but also a sense that perhaps this magnum opus summed up his outlook on life and death and nothing else would have the same impact. Either way, this monumental film is flawed and repetitive but consistently fascinating. A magnificent hi-def transfer elevates the lacerating closeups even higher. Lone extra is his short, Man in the Well.

Fritz Lang’s Indian Epic

(Film Movement Classics)

In the two films making up Fritz Lang’s Indian Epic—The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb—the exoticism of the Far East is colorfully if somewhat ploddingly brought to life by the legendary German director. Tiger is almost infuriatingly slow-paced, but the better-paced Tomb more organically delves into a culture unknown to many westerners.

A sparkling restoration gives the colors saturating depth on Blu-ray; extras are two commentaries, The Indian Epic documentary, and a video essay on star Debra Paget.

The Goldfinch

(Warner Bros)

Donna Tartt’s bloated and enervating novel somehow won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize, likely because its plot intersected the worlds of art and terrorism to nod toward being highbrow, even though Tartt’s is a distinctly middlebrow sensibility. Still, I held out hope for John Crowley’s film version since he showed such sensitivity and tact with 2015’s Brooklyn.

But this messy adaptation is a Cliffs Notes’ selection of highlights, nicely shot and acted (especially by Oakes Fegley as the younger self of hero Theodore, whose mother died in a Met Museum blast and who stole a small painting by a Dutch Master in the confusion) but narratively diffuse and often too literal-minded. The film looks superb in hi-def; extras are deleted scenes with Crowley’s intros and two featurettes.

I’ve never been a Jacques Rivette fan, except for the two films he made in the early ‘90s: 1991’s magnificently intimate, four-hour artist exploration, La belle noiseuse, and this even longer two-part study of Joan of Arc, released in 1994.

Starring Sandrine Bonnaire, in one of her greatest performances as the 14-year-old Joan (the actress was 26 while shooting), Rivette’s consistently engrossing historical drama clocks in at 5-1/2 hours, yet there’s not a dull or inopportune moment. The film’s restored hi-def transfer is richly detailed; too bad there are no contextualizing extras.

(Warner Archive)

Michael Anderson’s 1965 World War II drama gives a mainly fictional spin to the Allied operation where spies infiltrated a German factory involved in making the V1 and V2 rockets that were heavily damaging London and might do so to New York if the war continues.

Still, despite melodramatic touches (like Sophia Loren’s grieving but acquiescent widow of a man whom one of the spies is imitating), the film is entertaining and even at times exciting, and it authentically allows the actors to speak English, German or Dutch. It’s rare to hear so many bilingual name actors (George Peppard, Tom Courtenay, Anthony Quayle, Sophia Loren, Jeremy Kemp), providing welcome verisimilitude, which helps to smooth over the occasional silly moments. The film looks great in hi-def; lone extra is a vintage making-of.

Ready or Not

(Fox)

After a young woman marries her sweetheart at his family’s estate, they tell her she must partake in a “game” of hide and seek with her armed in-laws as a rite of passage that soon turns malevolent and murderous.

Samara Weaving makes for a most appealing heroine, but even she cannot save this benighted and obnoxious attempt at mixing humor and horror. There’s a very good hi-def transfer; extras include a making-of featurette, gag reel and a directors’ and star’s commentary.

Raise Hell—The Life and Times of Molly Ivins

(Magnolia)

Molly Ivins—the finest progressive journalist/political analyst of the late 20th century—is sorely missed in this era of corruption and gaslighting by the tRump administration that made the George W. Bush years look tame in comparison.

Director Janice Engel’s loving documentary portrait presents Ivins’ life, career and unique perspective (including her spicy sense of Texas humor) in its proper context, showing how progressivism has been in an uphill climb against entrenched corporate and conservative concerns in politics and media. Some of Ivins’ most stinging bits are included, along with heartfelt reminiscences by colleagues and figures who were the butt of her barbs. Extras are additional Ivins clips.

CD of the Week

Idina Menzel—Christmas: A Season of Love

(Schoolboy/Decca)

Idina Menzel—known by the public as the “Let It Go” singer from Frozen the movie and by those in the know as one of Broadway’s best singing actresses—returns with her second holiday album, matching her vibrant soprano with familiar yuletide tunes, from boppy openers “Sleigh Ride” and “The Most Wonderful Time of the Year” to classic hymns “Oh Holy Night” and “Auld Lang Syne.”

She also brings friends on board for fun duets on lesser-known ditties, including Billy Porter (“I Got My Love to Keep Me Warm”), Josh Gad (“We Wish You the Merriest”) and Ariana Grande (“A Hand for Mrs. Claus”). Other favorites are her take on the Peanuts standard “Christmas Time Is Here” and a song that name checks are young son, “Walker’s 3rd Hanukkah.”

December '19 Digital Week I

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 04 December 2019 04:01

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Blu-rays of the Week

The Bad and the Beautiful

(Warner Archive)

Vincente Minnelli’s 1952 Hollywood drama might not have the incisiveness of All About Eve or the darkness of Sunset Boulevard, but its story of a ruthless producer and those he uses along the way—including an actress, writer and director, all of whose tales we see—is an unalloyed delight, a sheerly entertaining glimpse of the movie business.

Kirk Douglas (producer), Lana Turner (actress), Dick Powell (writer) and Barry Sullivan (director) give the best performances of their careers, Charles Schnee’s script is witty and razor-sharp, and Minnelli’s direction is perfectly realized. Robert Surtees’ B&W photography looks especially sumptuous in hi-def; extras comprise the documentary Lana Turner: A Daughter’s Memoir and several score session cues.

The Battle of Leningrad

(Capelight)

The exhausting 900-day Nazi siege of Leningrad from 1941-43 is dramatized in this heroic but superficial war film that displays the horrors the Soviets went through but also their indomitable spirit while fighting a superior foe.

Although writer-director Aleksey Kozlov’s impressive physical production highlights the tension onboard a defenseless barge and its overflow crowd fending off German bombers, this otherwise standard-issue war drama gets most of its resonance by remembering those who died for their country. The movie looks spectacular on Blu.

Semper Fi

(Lionsgate)

Henry-Alex Rubin’s earnest if familiar melodrama about a police officer who’s also a Marine reservist who helps get his half-brother out of prison when he’s unfairly convicted wears its heart on its sleeve but can’t compensate for the script’s myriad clichés.

Mainly unfamiliar actors (excepting the always winning Leighton Meester) are unable to overcome the soggy writing and directing. There’s a fine hi-def transfer; extras are deleted scenes, featurettes and Rubin’s commentary.

Verdi—La Traviata

(Opus Arte)

Giuseppe Verdi’s classic opera about a famed courtesan is a dazzling showcase for a soprano, and Albanian singer Ermonela Jaho thrillingly goes for broke in her emotive characterization, so much so that she actually looks consumptively shrinking at the end of Richard Eyre’s handsome Royal Opera House (London) production.

As her lover and his father, respectively, Charles Castronovo and legendary Placido Domingo acquit themselves well. It’s adeptly conducted by Antonello Manacorda, leading the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Hi-def video and audio are first-rate.

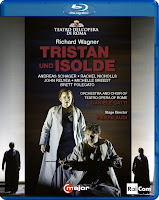

Wagner—Tristan und Isolde

(C Major)

Richard Wagner’s epic tragic romance has some of the most moving music ever written for the operatic stage—along with two of opera’s most punishing vocal parts. In Pierre Audi’s 2016 Rome staging, tenor Andreas Schager does wonders with minimal strain as Tristan, while soprano Rachel Nicholls does Herculean work as Isolde, especially in the draining, climactic Liebestod.

Conductor Daniele Gatti and the Orchestra del Teatro dell’Opera di Roma give an impassioned reading of Wagner’s massive score. Video and audio look and sound sublime in hi-def.

The World, the Flesh and the Devil

(Warner Archive)

Radioactive airborne matter has seemingly wiped out the earth’s population: except for a miner who was conveniently underground, played by Harry Belafonte. He goes to Manhattan to begin anew...but soon two others appear, and this thrown-together trio must deal with the end of civilization—and the possible beginning of another.

Belafonte, Inger Stevens and Mel Ferrer’s complex performances give director-writer Ranald MacDougall’s shallow “apocalypse drama” more gravitas than it deserves, but there are truly eye-opening views of a deserted New York City, including eerie shots of empty vehicles piled up on the George Washington Bridge and Lincoln Tunnel. Harold J. Marzorati’s B&W cinematography looks especially impressive on Blu.

DVDs of the Week

The Ground Beneath My Feet

(Strand Releasing)

Valerie Pachner’s persuasive portrayal of an employee of a powerful consulting firm whose personal and professional lives are put to the test when her mentally unbalanced sister’s condition worsens at the same time her work at the firm is given unfair scrutiny is the heart of Marie Kreutzer’s insightful character study.

Pachner dominates the screen in a physically and psychologically transfixing performance, whether she’s on a bracing run or dealing with discrimination from coworkers or the guilt she feels over her sister.

The Miracle of the Little Prince

(Film Movement)

Saint-Exupéry’s classic fable The Little Prince has survived since its 1943 publication (preceding the author’s death in World War II) as a work that children and adults of all ages love, but director Marjoleine Boonstra explores another aspect of its endurance in this forthright documentary.

The novella has been translated into hundreds of languages, including some on the brink of extinction, and Boonstra visits those who have translated the book into Tamazight (Morocco), Nahautl (El Salvador), Sami (Scandinavia), and Tibetan to record how it has allowed those languages to survive. If only the film wasn’t so long—it’s only 89 minutes, but reading excerpts and showing picture-postcard shots of the various landscapes do nothing but stretch the running time.

CDs of the Week

Neave Trio—Her Voice

Ethyl Smyth—Mass in D Minor

(Chandos)

In the 19th century, composers Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn were more famous for being attached to a more famous husband and brother, respectively. These two discs highlight a quartet of accomplished 19th and 20th century composers who happen to be women. Her Voice is the latest from the excellent Neave Trio, which eloquently performs spirited trios by three original voices: France’s Louise Farrenc (her 1843 trio), American Amy Beach (her 1938 trio) and Brit Rebecca Clarke (her 1921 trio).

The other disc brings together two works by British composer Ethel Smyth: the overture to her forceful 1904 opera The Wreckers and her Mass, a painstakingly realized work from 1891 (revised in 1925). Sakari Oramo skillfully conducts the BBC Symphony and Chorus and four fine soloists in her Mass.

Orchestre Metropolitain de Montreal Plays Carnegie Hall

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Tuesday, 03 December 2019 15:53

- Written by Jack Angstreich

November '19 Digital Week III

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Tuesday, 26 November 2019 19:08

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Blu-rays of the Week

All About Eve

(Criterion Collection)

One of the all-time Hollywood classics, Joseph Mankiewicz’s nasty, hilarious and witty satire of theater, movies and celebrities swept the 1950 Oscars and remains one of the most watchable movies ever made about show business. Bette Davis, Anne Baxter, George Sanders, Celeste Holm and Thelma Ritter are pitch-perfect, while Mankiewicz’s endlessly quotable script is a marvel of concision and bitchiness.

Criterion’s hi-def transfer is similar to Fox’s from 2011 and many extras from the Fox release (Mankiewicz documentaries, interviews, etc.) are included. Shockingly, Criterion’s packaging is shoddy: my booklet was torn since it was stuck to the foam knobs that hold the discs in place, and it’s difficult taking the discs out without worry about breaking them. It’s a rare whiff from what’s usually the best video company for packaging.

Ambroise Thomas—Hamlet

(Naxos)

French composer Ambroise Thomas premiered his adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in 1868, and it’s a spectacle of pageantry, tragedy, drama—along with a happy ending (Hamlet survives and becomes king). Despite that central absurdity, it’s a sturdy example of 19th century French grand opera, and director Cyril Teste’s 2018 Paris Opéra-Comique production looks and sounds terrific, including its use of onstage video.

Conductor Louis Langrée ably marshals the forces of the Orchestre des Champs-Elysées and Choeur Les Eléments, and the formidable cast is headed by baritone Stéphane Degout as Hamlet and a searing and emotional Sabine Devieilhe as the ill-fated Ophélie. The hi-def video and audio are tremendous.

Eegah

(Film Detective)

Nicholas Merriweather’s shoddy 1962 low-budget attempt at horror about a caveman who terrorizes a young woman, her boyfriend and her father is in Plan Nine from Outer Space territory as one of the worst movies ever made.

That’s apparently the selling point: this cheesy, laughable flick—containing several of the all-time amateurish performances—has been given a splendid hi-def transfer; extras include the Mystery Science Theater 3000 episode where the hosts crap all over it and interviews with MST3K creator Joel Hodgson and actor Arch Hall Jr.

The Fare

(Epic Pictures)

What starts as a shape-shifting Twilight Zone episode soon turns lugubrious as a cabbie and the young woman who keeps getting in—and disappearing from—the back seat try to discover why they’ve been thrown together.

Leading lady Brinna Kelly, also the scriptwriter, shows little facility in either role; leading man Gino Anthony Pesi is better but can’t create a character out of fragments; and director D.C. Hamilton can’t prevent the story from disappearing into the ether. There’s a crystal clear hi-def transfer; extras include a gag reel, deleted scenes, alternate opening, featurettes, interviews and commentaries.

Olivia

(Icarus Films)

In Jacqueline Audry’s 1950 drama, a young women’s boarding school is the setting for a series of physical and psychological clashes between factions of students and their headmistresses. Audry’s fresh and exuberant lesbian study never feels forced or false even when she’s up against the constraints of her era.

Her filmmaking is original enough for viewers to want to see what else she did—including her Colette-approved 1949 adaptation of Gigi—so one hopes more restored Audry films are forthcoming. The hi-def transfer of a new restoration is sparkling in B&W; lone extra is a vintage Audry interview.

Poldark—Complete 5th Season

(PBS Masterpiece)

In the engrossing final season of the latest television incarnation of Winston Graham’s classic novels, several years have passed since we last saw these characters, but the internal dramas and external political forces driving them remain forcefully and rivetingly intact.

As always, the remarkable cast—led by Aidan Turner (Ross), Eleanor Tomlinson (Demelza), Luke Norris (Dr. Enys), Gabriella Wilde (Caroline Enys), Jack Farthing (George) and Ellise Chappell (Morwenna)—propels eight hours’ worth of melodrama in the best sense. The directing, writing and physical production values are also first-rate. The hi-def transfer is transfixing; extras are several making-of featurettes.

This Is Rattle

(LSO Live)

In his first outing as music director, Simon Rattle conducts the London Symphony Orchestra in a sizzling program of British music from the 20th and 21st centuries, beginning with the delectable concert opener, Helen Grime’s Fanfares, and moving right into Thomas Adès’ Asyla and Harrison Birtwistle’s meaty, exceptionally difficult Violin Concerto, dispatched with aplomb by Christian Tetzlaff.

Rattle then guides his forces through Oliver Knussen’s thornily satisfying Symphony No. 3 before finishing with Edward Elgar’s magisterial Enigma Variations. Hi-def video and audio are top-notch.

Where’d You Go, Bernadette

(Fox)

Maria Semple’s 2012 novel about a middle-aged wife and mother who takes off after her artistic creativity has been stifled has been made by director Richard Linklater into a cutesy, enervating dramedy.

Cate Blanchett gives an unfocused performance in the title role and Kristen Wiig trots out her usual mannerisms as a next-door neighbor, while Billy Crudup and Emma Nelson’s earnest portrayals of Bernadette’s husband and teenage daughter are wasted. Even a finale set in Antarctica can’t save this wishy-washy display. There’s a fine hi-def transfer; extras comprise two making-of featurettes.

DVDs of the Week

The Corporate Coup d’Etat

(First Run)

Fred Peabody’s documentary ponders the corporatization of America—not only obvious stuff like Citizens United, but also the incremental ways that Democrats and Republicans have allowed individual liberties to erode and take a backseat to corporations and billionaires, setting us up for the disaster that is the tRump presidency.

You don’t have to agree with everything in the film by an array of talking heads from Matt Tiabbi to Cornel West to be incensed at how much in tatters our 200-plus year-old experiment in democracy is.

Queen of Hearts

(Breaking Glass Pictures)

Trine Dyrholm gives her usual masterly performance as a lawyer for battered and abused victims who has a torrid affair with her troubled 17-year-old stepson. Although director/cowriter May el-Toukhy doesn’t develop the intricacies of such unethical behavior as penetratingly as possible, Dyrholm’s incisive characterization greatly compensates.

Also noteworthy are Gustav Lindh as her young lover and Magnus Krepper as her husband, along with the raw but redundant sexual explicitness in the couple’s first encounter.

CD of the Week

Langgaard/Strauss—Orchestral Works

(Seattle Symphony Media)

The Seattle Symphony’s new music director Thomas Dausgaard capably leads the orchestra in works by Rued Langgaard and Richard Strauss in his first recording at the helm.

Dausgaard conducted the world premiere of Langgaard’s opera Antichrist, and the dynamic and unsettling prelude is a 12-minute orchestral tour de force. And Strauss’ An Alpine Symphony, a vigorous workout for large orchestral forces, is another aural triumph for Dausgaard and his talented Seattle ensemble.

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up