the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Reviews

Off-Broadway Play Review—Theresa Rebeck’s “Dig”

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Friday, 13 October 2023 01:26

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Dig

Written and directed by Theresa Rebeck

Performances through October 22, 2023

Primary Stages @ 59 E 59Theatres, 59 East 59th Street, NYC

PrimaryStages.org

.jpg) |

| Jeffrey Bean and Andrea Syglowski in Dig (photo: James Leynse) |

The always clever Theresa Rebeck’s play Dig awkwardly traverses psychological terrain without much plausibility. Set in a small-town plant shop, Dig follows its owner, Roger, a loner who's always run the place by himself but who hires a local pothead, Everett, to make deliveries. One day Roger’s longtime friend, Lou, who acts as his accountant of sorts, brings his wayward daughter Megan into the shop—she has just served time for a horrific crime and is also a recovering alcoholic. Roger and Megan make a reluctant connection, and she begins working at Dig, mostly of her own accord because Roger is unable to say she can’t.

From this contrived setup, Rebeck’s characters move around the beautifully appointed, if overstuffed, set by Christopher and Justin Swader like chess pieces manipulated by their author—there’s rarely any logic to their actions or their conversations. Roger and Megan’s budding relationship (unconsummated, according to her) never makes any psychological, dramatic or even comic sense, while a later attempted date rape by Everett after he and Megan go out drinking is quickly forgotten. When Megan’s ex-husband Adam, the actual perpetrator of the crime she took the fall for, confronts her before he marries someone else, nothing they say has any sting or depth. Rebeck piles up the obstacles for these people, particularly the shattered Megan, but they feel like mere contrivances for two hours.

Rebeck writes engaging dialogue but, in Dig at least (some of her earlier plays, like Seared and Seminar, were funny and perceptive), there’s little that’s insightful or piercing, especially since Rebeck directs without much distinction. When there’s a complaint about the shop’s name (which apparently might be confusing to perspective customers), it’s a bemusing moment, since anyone can look through the shop window, see the dozens of plants on display and figure it out.

Dig uses horticulture as an obvious metaphor for fixing psyches that, like the plants that Roger nurses back to health, may have been damaged beyond repair. But Rebeck never moves beyond the metaphorical to elucidate these individuals deserving of closer examination; it’s up to the game cast to, occasionally, make Dig both amusing and less trite than the material offers.

Greg Keller is always entertaining even if Everett is a mere plot device. Triney Sandoval as Lou and Mary Bacon as Molly, a repeat customer who becomes important in Megan’s life, and David Mason as Adam do what they can with considerably little. Jeffrey Bean, an assertive presence, nearly makes Roger into a comprehendible character.

That goes double for Andrea Syglowski who, in a nearly impossible role, invests so much of herself histrionically to clarify the contradictory Megan that she makes us sympathize with and even, almost, shed a tear for her. What Syglowski can’t do is dig Dig out of the hole the writer-director herself has buried it in.

October '23 Digital Week I

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Thursday, 05 October 2023 00:33

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Kidnapped (Rapito)

(Cohen Media)

The latest film by the world’s greatest living director, 83-year-old Italian master Marco Bellocchio, is yet another of his gripping and operatic dissections of historical subjects that touch on politics and religion—this time he tells the horrific but true story of a six-year-old Jewish boy torn from his parents’ grasp because a former housekeeper said she baptized him when she thought he was dying six years earlier. With his usual sweeping flair and acute observation, Bellocchio fills the screen with indelible images that not only cast a wide net on anti-Semitic mid-18th century Italian (read: Catholic) society but also the excruciating pain and loss felt by the Mortara family as their beloved son and brother remains forever out of their reach.

Bellocchio builds his film on two towering performances—by Barbara Ronchi as the boy’s mother and by Enea Sala as the six-year-old Edgardo, as strong a child performance I’ve ever seen. There’s also supremely well-chosen music by Rachmaninoff and Pärt to complement a superb original score by Fabio Massimo Capogrosso. Then there’s that haunting but gorgeous final shot of mother and son, as unforgettable as the rest of this masterpiece.

Kidnapped screens at the New York Film Festival on October 8 (FilmLinc.org); Cohen Media will release the film later this year or in 2024.

The Royal Hotel

(Neon)

As she does in the Netflix series Ozark, Julia Garner acts the hell out of her role as Hannah, one of two young American women who take a backpacking tour of Australia, where they become bartenders in a rundown Outback pub named the Royal Hotel—where they soon discover that the drinking culture down under is not as innocuous as it first seems.

Although Jessica Henwick matches Garner scene for scene as her friend Liv, Kitty Green’s thickly atmospheric drama is plenty short on plausible characterization or psychological coherence. When in doubt, blow something up—and Green follows that maxim, ending her film with a fiery inferno that’s a cheap way to satisfy her protagonists—and viewers.

(Cinema Epoch)

Charli and Zee’s fraught friendship that hangs on other men and—mostly—Charlie’s drug problem, exacerbated by her mental instability, is chronicled by writer-director Rich Mallery in a mainly exploitive manner: it seems as if most of the movie is an excuse to get several young actresses to undress in front of the camera.

It’s too bad, for Mallery’s heavy-handed approach hampers whatever credibility the otherwise interesting performers Kate Lý Johnston (Charli) and Kylee Michael (Zee) can invest in their roles.

(Magnet)

In a rural convent, a young nun is about to give birth to twins (she claims it’s by immaculate conception), one of whom will be the Messiah and the other the Antichrist, at least according to an old prophecy.

This alternately risible and effective slice of horror by directors Lee Roy Kunz and Cru Ennis has the dark, dank, relentlessly dour atmosphere down pat, but much of the rest is too pat—from the too-clever pun of the title and the wooden acting to silly contrivances like bludgeoning viewers from the start with beheadings and flayings that are too stylishly presented.

(Magnolia)

Folk legend Joan Baez receives an honest appraisal by directors Miri Navasky, Karen O'Connor and Maeve O'Boyle, who were given access to a storage unit’s worth of material that Baez’ mother had saved for decades, and which the singer herself didn’t even know was so voluminous. Baez tells her own story thanks to diaries she kept and letters she wrote since she was young, and there’s much archival footage (both commercial and home-movie) of Baez with her family and as one of the most celebrated singers and activists of our time.

Amid her commentary about everything from her ex Bob Dylan to her role in the civil rights movement, it’s her revelation that she and her late sister Mimi were abused by their father that will unsettle most viewers.

(Abramorama)

How the misperception of non-profits’ spending has caused untold damage to their ability to help those in need is chronicled by Stephen Gyllenhaal in an angry documentary that hopes to correct the unfair media coverage that led to congressional investigations and a massive loss of donations from a skeptical public.

Based on the eponymous book by Don Pollatta, who discusses how his own nonprofit became the target of scrutiny due to supposedly too-high salaries and overhead, the film also presents other nonprofit leaders who have felt the sting of public and governmental rebuke that hurt the people these charities try to help. It’s an eye-opening look at how cancel culture can hurt the very ones helping those who need it the most.

Creepy Crawly

(Well Go USA)

The perfect adjective for this bloody Thai horror flick is the first word of its title—creepy is the only way to describe the plot, which concerns an ancient, centipede-like monster inhabiting its guests at a hotel where they are quarantining during a pandemic. The creature burrows into its victims and takes over their bodies to gorily spectacular effect.

Writers-directors Chalit Krileadmongkon and Pakphum Wongjinda push the envelope with an unblinking emphasis on more blood and guts, and the game cast goes along with it, right up to the finale. There’s a first-rate hi-def transfer.

(Dreamworks)

In Dreamworks’ latest animated feature, young Ruby has difficulty fitting in among her fellow teens at school once she learns that she’s a sea kraken—and that her best friend is actually a mermaid, the mortal enemy of the kraken.

There’s plenty of amusement and sentiment in Ruby’s plight, and it comes with a colorful visual palette overseen by director Kirk DeMicco and codirector Faryn Pearl, along with sparkling voice performances by Lana Condor (Ruby), Toni Collette (her mom) and the redoubtable Jane Fonda (kraken matriarch Grandmamah). It looks eye-poppingly pleasing on Blu; extras include an audio commentary, deleted scenes with Pearl’s intro, interviews and featurettes.

Schreker—Der Schatzgraber/The Treasure Hunter

(Naxos)

Austrian composer Franz Schreker (1878-1934) wrote many operas, and although none has gained a foothold in the repertory, this convoluted drama concerning magic jewels, murder and redemptive love is about as close as he came to a popular work—at least until his exquisite music was banned by the Nazis.

Director Christof Loy’s 2019 Berlin staging leans into the forceful melodrama that Schreker builds through his provocative plot and luminous score as well as the juicy roles for the leads; Daniel Johanson and Michael Laurenz are excellent as the male leads, but it’s Elisabet Strid’s portrayal of the heroine that makes this so tragically memorable. Marc Albrecht persuasively conducts the Berlin Opera Orchestra.

Slava Ukraini

(Cohen Media)

French philosopher Jacques Henri-Levy went to Ukraine right after the Russian invasion and spent months visiting several regions affected by Putin’s unprovoked belligerence, speaking with both civilians and soldiers defending their homeland against the onslaught.

Henri-Levy’s interactions provide affecting and personal responses and reactions from a population that, even under heavy bombardment, won’t surrender, and the film is a window into and map of how the Ukrainian people are coping with and even returning fire to Putin’s murderous thugs. Lone extra is a post-screening Q&A with Henri-Levy.

September '23 Digital Week III

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 27 September 2023 22:38

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Early Short Films of the French New Wave

(Icarus)

This valuable two-disc set collects short films from French directors of the New Wave and surrounding names from the fertile 1950s, in which big shots like Godard, Truffaut, Chabrol and Varda are represented (including A Story of Water, a collaboration between Godard and Truffaut).

The highlights are two Alain Resnais classics—All the Memory in the World and Le Chant du Styrene, masterpieces in miniature—and a pair from Maurice Pialat, Love Exists and Janine. All 19 films have been restored and look magnificent on Blu, even though several (including the Resnais films) are available elsewhere on other releases, so your mileage may vary.

(Lionsgate)

In director Samuel Bodin’s eerie but clumsy debut feature, eight-year-old Peter doesn’t think his parents are what they seem and, after hearing the voice of someone behind his bedroom wall, he’s even more suspicious. The first half of this 90-minute movie is creepily effective but once Bodin and writer Chris Thomas Devlin decide to overload on obvious jump scares, it becomes impossibly risible.

Woody Norman is a properly intense Peter, but the gifted and usually impressive Lizzy Kaplan is hampered by a clichéd mom role that she can do nothing with. The film looks good on Blu; extras are three short making-of featurettes.

(Music Box)

In Emanuele Crialese’s precisely observed character study, Penelope Cruz plays Clara, a harried Spanish mother with three kids and a philandering husband in 1970s Rome who tries her best to deal with Adriana, her oldest child, who identifies as a boy named Andrea: Clara and her child, both outsiders, form an even closer bond, as does Andrea and Sara, a young Romani girl who’s also an outsider.

Although Crialese’s elaborate musical numbers that comment on the characters’ psychology are superfluous, he gets wonderful acting from the entire cast, especially the subtle portrayal of Andrea by Luana Guiliani. There’s an excellent hi-def transfer.

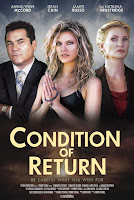

Condition of Return

(Stonecutter Media)

After Eve Sullivan shoots up a church during services, Dr. Donald Thomas interviews her to find out her motive—and her story makes up the bulk of this confused and gratuitous melodrama about how someone good can do something evil. Hint—it’s a deal with the devil.

Although AnnaLynne McCord persuasively plays Eve, she’s pitted against an unrecognizably bloated Dean Cain as Dr. Thomas (he phones in his performance) as well as director Tommy Stovall and writer John Spare, who cram so many unlikely contrivances and banal “ironic” twists into the plot that they must have come up with their own deal with the devil to get this made.

(Greenwich Entertainment)

Director Philip Carter’s fascinating documentary chronicles the last word in subterfuge from the CIA—with help from major misdirection in the form of a cover story from none other than reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes—as it raised a stricken Soviet nuclear sub from the ocean depths over a six-year period (1968-74), during the heart of the Cold War.

Through vintage footage and interviews with many of the principals—including the agency’s own David Sharp, prime mover behind the operation—this incisive portrait of a real-life government espionage also plays out like an urgent, nail-biting thriller—which, in some sense, it is.

(Film Forum)

Ulises De La Orden’s engrossing three-hour documentary exclusively comprises videotape footage of the trials in Argentina of the leaders of the military junta who spearheaded the “disappearing” of thousands of individuals considered enemies of the government from 1976 to 1983. Leftists and other democratic sympathizers were tortured and often murdered, and the men responsible for the coup and systematic annihilation of so many of their fellow countrymen are given the opportunity to defend themselves, unlike their victims.

Whittling down hundreds of hours of footage from the courtroom into three fascinating, enraging, often breathless hours, de la Orden allows those who were affected and survived to speak for both themselves and those who never returned. As the prosecutor says at the end of the trial, “Nunca Más” (never again).

(Film Movement)

The background of Fellini’s classic film La Dolce Vita comes alive through this engaging documentary portrait of one of its producers, Giuseppe Amato, who not only had to fight the director himself about its length, editing and premiere, but also the film’s distributor Angelo Rizzoli.

Director Giuseppe Pedersoli’s reenactments fall flat, as doc reenactments almost always do, but his interviews with key characters in the story, including Amato’s widow, colleagues and film historians, present a key glimpse into Italian cinema that’s worth watching.

(Gravitas Ventures)

Ashley Avis, who directed the 2020 Black Beauty remake, has made an urgent and timely documentary plea for the wild horses that roam across America’s western plains who are in danger of disappearing thanks to the government’s heavy-handed policies that are anything but humane.

Avis surreptitiously films the Bureau of Land Management’s barbaric culling episodes and unapologetically gets into the faces of the bureau’s spokespeople to discover what’s really going on. There’s a lot of justified anger and emotion underlining Avis’ stunningly photographed film, which shows the natural beauty of these majestic animals, who are shortsightedly under siege.

Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!

(Chandos)

It’s hard to believe that one of the great Broadway musicals, beloved and worshipped since its 1943 Broadway premiere and the classic 1955 film with Gordon MacRae as Curly and Shirley Jones as Laurey, has never before been heard in its entirety in a recording but that’s what this new release screams on the front cover: “world premiere complete recording.” In their first collaboration, Rodgers & Hammerstein outdid themselves with so many memorable and hummable songs, from the opening “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” to the climactic title tune.

The Sinfonia of London, led by conductor John Wilson, gives Richard Rodgers’ glorious score a high polish, while the cast—including a formidable chorus—sings Oscar Hammerstein’s lyrics beautifully. Best of all is Sierra Boggess, who may be the most pure-voiced Laurey that I’ve yet heard. This Super Audio CD has, unsurprisingly, wonderfully spacious sound.

September '23 Digital Week II

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 20 September 2023 01:23

- Written by Kevin Filipski

The Exorcist

(Warner Bros)

Still as shocking as it was 50 years ago, William Friedkin’s adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s crassly entertaining novel is a punch to the gut that works brilliantly, even after many viewings, because of its artful misdirection. You expect nasty shocks, but the slow build-up lulls you into believing you’re watching a docudrama about a young girl whose odd behavior eventually has no other explanation but the supernatural. When the horror arrives, it’s been grounded in such vivid reality that more is at stake than a simple “good vs. evil” battle: it’s personal.

This terrific 4K release contains the original—and still superior—version and the director’s cut, both looking splendid in UHD: Friedkin and cameraman Owen Roizman’s documentary-like touches accentuate the eeriness. And Friedkin’s expertly chosen music (Penderecki, Henze, Webern, “Tubular Bells”) sounds superb. Extras are commentaries by both Friedkin and Blatty as well as Friedkin’s introduction.

(Criterion Collection)

One of Orson Welles’ most dazzling visual achievements is his 1962 adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel about everyman Josef K., who’s the unwitting target of the totalitarian regime that arrests and condemns him for an unnamed crime. Although the narrative at times gets sticky, the director is in his expressionist element, cinematographer Edmond Richard’s haunting B&W images complementing Welles’ off-kilter and off-putting camera angles, editing and music choices.

The main quibble is a rather stolid Anthony Perkins in the lead. Criterion’s release contains a superb UHD transfer, Welles expert Joseph McBride’s commentary, an archival interview with Richard and two with Welles: one with Jeanne Moreau (who’s in the film) and one at UCLA in 1981.

American—An Odyssey to 1947

(Gravitas Ventures)

Danny Wu’s documentary begins by taking a well-trodden path showing Orson Welles’ early life as a child prodigy through his first theater success and infamous War of the Worlds broadcast until it all falls apart following Citizen Kane and his Hollywood career dwindled to nothing after the abortive Magnificent Ambersons debacle. Wu then turns to two little known men: Japanese-American Howard Kakita (who survived the bombing of Hiroshima as a child) and Black serviceman Isaac Woodard (who was beaten so badly upon his return to the South after WWII that he was left permanently blinded).

Wu’s attempt to tie the stories of these disparate men together is often clumsy, for Welles’ artistic genius keeps getting in the way. (Even Welles’ discussion of Woodard is eloquent.) But Wu’s interviews with several talking heads—including Kakita himself—illuminate a necessarily expansive definition of the term “American.”

From the mischievous Australian sibling duo known as Soda Jerk, this lacerating critique of America during the Trump years is cleverly reedited from various repurposed scenes from dozens of unrelated films—including American Beauty, Wayne’s World, Robocop (which features the most pointed satire of today’s society), A Nightmare on Elm Street, Peggy Sue Got Married, etc.—which are tweaked to show how trump supporters and Hilary supporters acted during that fraught and, in hindsight, ridiculous and dangerous time.

The problem with the film is that it’s one-note: for all its humor and even insight, after about a half-hour, it starts to become redundant; we all know what happened—the reality was worse than any reedited bunch of film scenes and overdubs could make it—so why subject ourselves to it again?

(Magnolia)

The fascinating life of Bethann Hardison, who was one of the first Black supermodels and became an agent and, later, activist who paved the way for the stellar careers of such models as Iman, Naomi Campbell and Tyra Banks, is chronicled in this breezy but substantive documentary by directors Frédéric Tcheng and Hardison herself.

Hardison, of course, is refreshingly candid in nearly every sound bite and video clip over the decades; her son, actor Kadeem Hardison, Iman, Campbell, and Ralph Lauren, among others, speak touchingly and honestly about a trailblazer who became a lasting influence on the modeling profession for so many, whether they realize it or not.

(Kino Lorber)

Iconoclastic author Tom Wolfe—who coined such popular phrases as “the me decade,” “social X rays,” and “radical chic”—is remembered in Richard Dewey’s succinct but too brief (only 76 minutes!) documentary based on a Vanity Fair article by Michael Lewis, one of several admiring colleagues, associates, and family and friends who are interviewed about the author of The Right Stuff and The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Wolfe died at 88 in 2018, with his best work and cultural relevance behind him, but Dewey’s interviewees are sure his writing will endure; historian Niall Ferguson says it will be reevaluated and rediscovered by readers interested in what America was like in the last half the 20th century.

Don Pasquale

(Opus Arte)

One of Gaetano Donizetti’s delightful comic operas has been given a rollicking production by director Damiano Michieletto at London’s Royal Opera House in 2019; the humor is intact and the relationships are pointedly presented.

The great baritone Bryn Terfel makes a perfect Pasquale, and he is surrounded by a wonderfully capable cast that’s led by the winning Russian soprano Olga Peretyatko as love interest Norina. It’s all conducted with panache and verve by Evelino Pido, who leads the Royal Opera orchestra and chorus. There’s first-rate hi-def video and audio.

(C Major)

French composer Charles Gounod’s tragic opera follows Shakespeare’s classic play fairly closely after beginning with the coffins of the star-crossed lovers onstage—and Gounod’s enchanting melodies magnificently mirror Shakespeare’s poetry, especially in the lyrical scenes between the pair.

Russian soprano Aida Garifullina is a meltingly lovely Juliette and Albanian tenor Saimir Pirgu is a charming Roméo, with conductor Josep Pons leading a reliable reading of the music by the orchestra and chorus. Director Stephen Lawless’ 2018 Barcelona staging catches the sense of young romance and impending tragedy. The hi-def video and audio are enticing.

Succession—The Complete Series

(HBO/Warner Bros)

This compelling and hilarious series about ultrarich corporatists chugged along for four always watchable seasons, including the shocking but inevitable plot twist early in the final season that finally provided a real conclusion to what the title hinted at. The tension between a successful media corporation’s founder, Logan Roy, and his adult children, all of whom are in one way or another unworthy to succeed him—sons Kendall, Roman and Connor as well as daughter Shiv—reaches heights of tragicomedy worthy of Shakespeare.

The superb writing is complemented by the magisterial acting, from Brian Cox, who plays the Lear-like Logan, to Jeremy Strong (Kendall), Kieran Culkin (Roman), Sarah Snook (Shiv) and the scene-stealing J. Smith-Cameron as the family’s shrewd associate Gerri. All 39 episodes are included, along with several featurettes and interviews, but it's too bad that this addictive series (which was shot on film) has not been released on Blu-ray, let alone 4K.

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up

Upcoming Events

No Calendar Events Found or Calendar not set to Public.