the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Reviews

Summer 2023 Tanglewood Concerts—Elvis Costello, Robert Plant/Alison Krauss, James Taylor

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Thursday, 17 August 2023 16:08

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Elvis Costello and the Imposters

Saturday, July 1, 2023

Robert Plant and Alison Krauss

Sunday, July 2, 2023

James Taylor

Monday, July 3, 2023

Tanglewood

Lenox, Mass.

Performances through September 3, 2023

bso.org/tanglewood

Nestled in the bucolic Berkshires in western Massachusetts, Tanglewood has been the go-to summer destination for outdoor classical performances for decades; the Boston Symphony Orchestra has made its summer home there since 1937. Occasionally, even rock and pop artists perform there as well; this summer, fortuitously on the first three nights in July, concerts by several veterans were a great reason to go back up there for the long Independence Day weekend.

.jpeg) |

| Elvis Costello at Tanglewood (photo: Hilary Scott) |

First up was the return of Elvis Costello and the Imposters—including stalwarts Steve Nieve on keyboards and Pete Thomas on drums as well as special guest Charlie Sexton, who started as a teen guitar whiz and now, three decades later, is simply a guitar whiz—for a scintillating 2-1/2-hour set that comprised every part of Costello’s long and winding, nearly five-decade long career.

From the propulsive opener “Mystery Dance,” Costello gave impassioned renditions of many two dozen songs from his impressive songbook, from early classics “Radio Radio” and “Alison” to middle-period gems “Uncomplicated” and “Everyday I Write the Book” to a trio of tunes from his excellent 2022 album, The Boy Named If (including a raucous “Magnificent Hurt”). Costello’s in-between song patter is as pointed and hilarious as ever, as when he talked about hearing Bruce Springsteen for the first time as a teenager and thinking he was Dutch. The Imposters’ romp to the finish was particularly astonishing: after a weird and overlong “Watching the Detectives” and a thunderous “Lipstick Vogue,” Costello closed with his raw, angry, emotionally naked dirge “I Want You,” which he seemed to know could not be topped. He didn’t try.

.jpeg) |

| Alison Krauss and Robert Plant at Tanglewood (photo: Hilary Scott) |

The next night, it was Robert Plant and Alison Krauss’ turn to grace Tanglewood’s Koussevitzky Music Shed stage. Plant and Krauss together took the music world by storm when their 2007 album of rootsy bluegrass/country/folk hybrids, Raising Sand, was a huge success, selling millions and winning Grammys. The pair released a solid second album, Raise the Roof, in 2021; the 90-minute concert was what you’d expect: 15 tunes that hinged on the beautiful blending of Plant’s weathered but still supple voice and Strauss’ gracefully twangy soprano and supplemental fiddle stylings.

Although the boisterous crowd roared loudest for the four Led Zeppelin tunes placed throughout the set—of which the elegiac duet “The Battle of Evermore,” sung sublimely by both, was the obvious highlight (although a thumping “Gallows Pole” came close)—each song was an exquisitely crafted gem, including a non-Zep Page/Plant original, “Please Read the Letter,” and the closing “Gone Gone Gone.”

%20(2).jpeg) |

| Henry Taylor and James Taylor at Tanglewood (photo: Hilary Scott) |

James Taylor’s Tanglewood appearances have become an annual event—or events: he performed July 3 and July 4—bringing fans both young and old, parents and their kids (and even grandkids) together for joyful singalongs. To start the show, on screens there’s a video spanning Taylor’s 50-plus years singing his debut single, “Something in the Way She Moves,” from 1968 to the present day, when he takes the stage to finish the song live. His voice is noticeably strained but still a versatile instrument, and his humorous side came through in his chatty patter throughout the performance.

Featuring an ace backing band that included his wife Caroline and son Henry on backing vocals, Taylor’s career-spanning concert mixed enduring classics like “Sweet Baby James,” “Carolina in My Mind” and the lacerating “Fire and Rain” with lesser-known tunes like “Mona” (about a pig) and “Secret o’ Life.” He ended the show singing with just Henry, two generations of Taylors sharing vocals on the father’s lovely lullaby, “You Can Close Your Eyes.”

August '23 Digital Week II

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 16 August 2023 13:53

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Passages

(MUBI)

Ira Sachs has made sympathetic and insightful portraits of relationships, but his latest is not among them. In Paris, selfish German film director Tomas leaves his longtime English husband Martin after falling for Agathe, a young French woman from around the set whom he has sex with after the wrap party. Soon, however, he comes back to Martin—then back to Agathe…rinse repeat.

There’s no denying Tomas is a manipulative narcissist, but the response to his antics by Martin and Agathe (who gets pregnant immediately, of course) are so preposterous that they become risible. Very little of this is in any way fascinating—even the lengthy and explicit sex scenes are quite boring—and the acting is a mixed bag. Adele Exarchopoulos is always an honest and humane performer, Ben Wishaw does what he can with an impossible part and Frank Rogowski trots out his tiresomely surly number whatever the role calls for.

The Strange Mister Victor

(Grasshopper)

Two films by the masterly but barely known French director Jean Grémillon have been fully restored, each showcasing the filmmaker’s singular observational skill within the context of intelligently tweaked genres. 1937’s romantic saga Lady Killer stars the great Jean Gabin as a seducer who falls in love with his latest conquest, played by the exquisite Mireille Balin.

The following year, Grémillon’s crime thriller The Strange Mister Victor stars actor Raimu as a shopkeeper working secretly for the underworld whose criminal activities soon catch up to him. Here’s hoping more of Grémillon’s features are restored and rereleased.

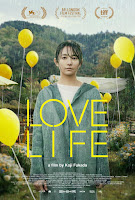

(Oscilloscope)

Like his last drama, the diverting A Girl Missing, Japanese director Koji Fukada tells a downbeat story that’s filled with redemption in his usual slowly evolving manner, anchored by Fumino Kimura’s elegantly restrained performance as a woman who, after a tragic family accident, starts to care for her former husband, who’s deaf and homeless.

As is the case once again here, Fukada makes messy but heartfelt films that are closely observed and deal with sorrowful subject matter quite convincingly.

(Saban)

Writer-director Nicholas Maggio said that Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs made him want to make similar movies when he saw it as a teen in the early ‘90s—but on the basis of this turgid crime drama, whatever originality Tarantino brought to the genre is completely missing in Maggio’s hands.

Unlucky rural Louisiana robbers are tracked down by a brutal New Orleans mob fixer, and the bodies start piling up. Stephen Dorff has fun playing the horrible hitman but John Travolta, Shiloh Fernandez and Ashley Benson are defeated by their director’s caricatures and his unoriginal melodramatic flourishes.

(Rialto)

In this completely whacked-out 1979 political thriller-cum-satire, Jeff Bridges plays the younger half-brother of an assassinated president trying to find out who killed him—but he’s up against the deep state, which might include his own father, a Joe Kennedy-type tycoon played with gusto by John Huston.

Director William Richert, adapting a novel by Richard Condon, is somehow able to walk the tight rope between straightforward drama and jokey lunacy, although another 20 minutes would flesh out the contorted conspiracies a la The Parallax View. Bridges is in his usual fine form and the colorful ensemble includes the smashingly good Belinda Bauer as an atypical femme fatale.

Fast X

(Universal)

The 10th “fast and furious” feature might have some fury but not much that’s fast in a lumbering two-plus hour adventure that repeats the car chase/close combat sequences done to death in the series’ other entries.

Director Louis Leterrier makes things fancier with some amusing destruction of Rome, particularly at the Spanish Steps, but with so many random characters being introduced the usual cast can’t get any traction. Even luminary guest stars like Helen Mirren, Rita Moreno and Charlize Theron have embarrassingly little to do. The film looks terrifically detailed in 4K; extras include over an hour’s worth of featurettes and a gag reel.

Broken Mirrors

(Cult Epics)

In Dutch director Marleen Gorris’ provocative 1984 drama, several female sex workers at a brothel must deal daily with their anonymous, enervating, antagonistic male clients; meanwhile, one of those men is killing random women and has kidnapped a housewife off the street.

As her other films (such as A Question of Silence and Antonia’s Line) have shown, Gorris is unafraid to bluntly explore and raise unsettling questions about what it means to be a woman in a brutish man’s world. There’s a decent new restoration; extras are a commentary by film scholar Peter Verstraten and archival interview with sex worker Margo St. James.

(Well Go USA)

Shot in the beautiful, rugged terrain of Montana’s Big Sky country, Ari Novak’s thriller doesn’t have much else to recommend it, beginning with its by-the-numbers plot about a grieving Navy seal accompanying a young woman to bury her father’s ashes finds trouble after stumbling on a cache of cash murderous terrorists are after.

Novak stages the shoot-‘em-up sequences with little distinction, while his actors can barely read their lines. Leads Rib Hillis and Rachel Cook were obviously cast for how good they look sans clothing—Rib is ripped while Rachel is often stripped down to her bra and underwear—which might make for a fun drinking game to get through the 90 minutes of amateurish storytelling that desperately throws in easily guessable twists to wrap up. The film looks great on Blu, at least.

(Music Box)

Winner of the César (the French Oscar) for best actress for her brilliant performance in Revoir Paris as a mass-shooting survivor, Virginie Efira performs a similar miracle in this intensely intimate study as Rachel, a childless schoolteacher who loves Leila, the young daughter of her boyfriend Ali (Roschdy Zem), as if she was her own—until his ex-wife initiates a reunion that might squeeze Rachel out of their lives altogether.

Rebecca Zlotowski’s delicate writing and directing provide Efira with another showcase for her emotionally shattering acting; ideally, she should have won the César for both of her draining portrayals. There’s an excellent Blu-ray transfer; extras include a featurette with Zlotowski, Efira and Zem interviews as well as a Toronto Film Festival Q&A with Zlotowski and Efira.

Sounds and Sweet Airs—A Shakespeare Songbook

(BIS)

Soprano Carolyn Simpson and pianist Joseph Middleton’s recital discs are always meticulously curated—and their latest might be their most impressive and enjoyable yet. They’re joined by baritone Roderick Williams for a wide-ranging literary and musical journey through songs written to texts in Shakespeare’s plays. The three artists move through three centuries of great composers—programmed as a prologue, acts I-V and an epilogue—from the 18th century’s Thomas Arne to two powerful 21st-century pieces: Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s “They Bore Him Barefaced on a Bier” from Hamlet and Hannah Kendall’s song-cycle Rosalind based on texts from As You Like It, in which Simpson not only sings stirringly (alone and duetting with an equally strong Williams) but also plays the music box and harmonica.

We also get the chance to hear composers tackling the same text, like The Tempest’s “Full Fathom Five,” set by John Ireland (as a duet!) and by Michael Tippett (for baritone). My favorites are settings by Vaughan Williams, Parry and Honegger, along with Rosalind, where Kendall captures the deepest emotions in Shakespeare’s luminous poetry.

August '23 Digital Week I

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 09 August 2023 21:56

- Written by Kevin Filipski

In-Theater/Streaming Releases of the Week

Afire

(Janus Films)

German director Christian Petzold’s “elements” quartet began in 2020 with his “water” film, Undine. The second, Afire—the German title, Roter Himmel, means Red Sky, which is also a more evocative English title—is an off-kilter comedy of manners about a pretentious author, Leon, who spends time with his friend Felix at Felix’s family’s summer cottage to finish his latest book. Leon meets Nadja, also staying there, who uncouples him from his own narrow perspective and forces him to face hard truths about himself, all while deadly—both real and metaphorical—forest fires are sweeping the region.

Petzold’s script and direction are surprisingly none too subtle, but he’s able to sell this often predictable, even silly story through his exemplary cast, led by Thomas Schubert’s self-absorbed Leon and the luminous Paula Beer—now Petzold’s post-Nina Hoss muse—as the seemingly guileless Nadja.

(Greenwich Entertainment)

In Rodrigo Sorogoyen’s slow-burn drama, French couple Antoine and Olga grow eco-friendly crops in rural Spain among poor farmers suspicious of their motives, especially after they vote against allowing a wind-energy company to purchase local land, which would give many the cash they desperately need.

Although it goes on way too long—its plot could easily unfold in an equally anxious manner with a half-hour cut out—Sorogoyen gets remarkable performances by Luis Zahera and Diego Anido as brothers who become the couple’s worst antagonists, Denis Ménochet as Antoine and especially Marina Foïs, who, as Olga, gives a master class in understatement, especially in the extraordinary close-up with which Sorogoyen smartly ends his film.

(Moira Productions)

In his raw, emotional cinematic memoir, Tom Weidlinger candidly explores the secrets and lies haunting his family, starting with the reminiscences of his father, a Hungarian scientist who survived the Holocaust: something that he had hidden from his children.

Although I generally abhor reenactments in documentaries, here they perfectly underscore the unsettling state Weidlinger finds within himself trying to pull apart the truth from the fiction in his family’s history.

(Music Box Films)

Lily Gladstone—soon to be seen in Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of Killers of the Flower Moon—gives her usual persuasive, natural performance in this too often diffuse character study by writer-director Morrisa Maltz. Gladstone plays Tana who, coming off a crushing personal loss, attends a family wedding on the Lakota reservation then takes off on a road trip to try and find some sort of closure.

What follows is meandering and intermittently absorbing, but when, along the way, as Tana meets real people living real lives, Maltz has them narrate their own stories, which have a way of obscuring Tana’s own journey. Even the final, stunning location shots of Tana ultimately feel unearned.

East of Eden

(Warner Bros)

Elia Kazan’s 1955 adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel based on the Biblical story of Cain and Abel, here in the form of opposing brothers Cal and Aron only occasionally crackles to life, instead teetering under Kazan’s ponderous direction.

The cast is impeccable, however, led by James Dean in his memorable film debut as Cal; Raymond Massey as the boys’ dad; Jo Van Fleet as their long-lost mother; and Julie Harris as the young woman wanted by both brothers. Ted McCord’s color photography looks especially sharp on UHD; lone extra is critic Richard Schickel’s commentary.

(Warner Bros)

The 1973 movie that made Bruce Lee an international star—and which was released posthumously, soon after his shocking death that summer at age 32—is a relatively lean action flick with some narrative dead ends that spends most of its time on eye-popping kung fu skirmishes.

Lee was a magnetic screen star without being a decent actor—his exciting physicality was his calling card. The UHD transfer is crisp and clear; extras include a producers’ commentary and a short intro by Lee’s widow, Linda Cadwell.

(Warner Bros)

Howard Hawks’ 1959 western is considered one of the best entries of the genre; despite the presence of John Wayne, who plays the heroic sheriff with his usual laconic sameness, it’s an entertaining, exciting drama about a small group of good guys fending off a murder suspect’s armed gang.

Good acting by Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, Angie Dickinson and Walter Brennan makes up for Wayne’s one-note presence. The stunning vistas, photographed by Russell Harlan, look even more spectacular in 4K; lone extra is a commentary by critic Richard Schickel and director John Carpenter.

Mussorgsky—Boris Godunov

(Opus Arte)

Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky’s operatic masterpiece about the infamously murderous czar is usually performed in Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s reorchestrated version, but Kasper Holten’s 2016 Royal Opera staging reverts to Mussorgsky’s original stark vision with gripping results.

Welsh bass-baritone Bryn Terfel is a mesmerizing Boris, especially in the tragic climactic scene; Antonio Pappano superbly conducts the Royal Opera House Orchestra and Chorus, the latter triumphing in the composer’s haunting vocal lines. As usual, hi-def video and audio are first-rate; lone extra is a conversation about the opera between Terfel and Pappano.

(Dynamic)

Igor Stravinsky’s challengingly austere oratorio, with a text by Jean Cocteau from Sophocles’ play, has divided listeners since its 1927 premiere: this 2022 concert version from Florence, Italy, conducted by Daniele Gatti, finds its power in the all-male chorus, AJ Gleuckert’s Oedipus, Alex Esposito’s Creon and Ekaterina Semenchuck’s Jacosta.

As a wonderful bonus, Gatti and the orchestra also perform Italian composer Ildebrando Pizzetti’s moody Three Orchestral Preludes, also composed for Sophocles’ play. There’s stellar hi-def video and audio.

Wilhelm Grosz—Achtung, Aufnahme!!

(Channel Classics)

German composer Wilhelm Grosz (1894-1939) wrote music tinged with jazz rhythms—his short and witty 1930 one-act opera Achtung, Aufnahme!! (Attention, Recording!!), a supreme example of its era, contains sparkling singing and musicianship in a recording made over several years (1999 to 2005) by Ebony Band and its conductor Werner Herbers, who died earlier this year.

Kudos also to several vocalists and the Cappella Amsterdam led by Daniel Reuss. Also included on this world-premiere recording are two short dramatic works: Komödien in Europa (Potpourri) by Walter Goehr and Die vertauschten Manuskripte (Potpourri) by Mátyás Seiber, less scintillating than Grosz’ work but still highly listenable.

(BRKlassik)

German composer Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) wrote one great opera—Mathis der Maler—and several less successful dramatic works, including this strange but often compelling 1926 tale of a goldsmith whose jewelry customers mysteriously are killed.

This 2013 recording, while less memorable than others—including the classic DG one starring the great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in the title role—has fine performances by the Prague Philharmonic Choir and Munich Radio Orchestra under conductor Stefan Soltesz (who died a year ago) and a solid cast led by Markus Eiche as Cardillac and Juliane Banse as his daughter.

July '23 Digital Week III

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 26 July 2023 12:39

- Written by Kevin Filipski

The Last of Us—Complete 1st Season

(Warner Bros)

The first HBO series based on a video game (for what it’s worth), this dystopian thriller isn’t very original—the visuals of this post-pandemic world are awfully familiar, as are the zombie-like victims of a fungal infection that’s destroyed civilization as we know it—but it gets by on clever writing and sympathetic acting, which makes the characters more human than usual in this genre.

Led by Pedro Pascal, there are also formidable performances by Bella Ramsey, Nico Parker and Anna Torv: but there’s a sense that, after nine one-hour episodes—and a second season to come— the redundancy will take over soon. The hi-def transfer looks good; extras comprise several making-of featurettes, interviews and on-set footage.

(Shudder)

I don’t think we need another found-footage horror flick at this late date, but at least writers/directors Vanessa and Joseph Winter’s foray into the genre, about a disgraced YouTuber (is there any other kind?) who goes to a supposedly haunted house, has a sense of humor about itself that sustains it for at least the first half before it ends up repeating itself to death, so to speak.

The film looks quite good in hi-def; extras include several featurettes, bloopers, deleted and alternate scenes, interviews, on-set footage and a commentary.

(Lionsgate)

Writer-director-star Charlie Day (best known for It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia) has delivered a fool’s errand with this completely hamfisted Hollywood satire about a mute just released from a mental hospital, a dead ringer for a famous actor, who gets into the movie business almost accidentally.

It’s an ungodly mix of Being There and Mr. Hulot’s Holiday, and Day is not a good enough actor—or writer or director—to pull it off successfully, let alone competently. Even good actors like Edie Falco and Kate Beckinsale are unable to overcome the soggy script and middling direction, and one-dimensional performers like Jason Sudekis fall back onto their usual tricks. The film looks decent on Blu.

(Universal/Open Road)

Gerard Butler gives another solid if unexceptional performance in his second 2023 action thriller, but unlike the faceless Plane, Ric Roman Waugh’s film has a bit more bite for a timely excursion into the murderous world of Middle Eastern double-dealing and revenge.

Although there’s nothing new here and it goes on too long, Kandahar does have its share of tense sequences, and Butler’s stoic heroism is well-suited to the role of a CIA operative desperate to save his Afghan translator and get home to his own teenage daughter. There’s a terrific hi-def transfer.

(Cohen Media)

In the most contrived way possible, director Vadim Perelman has made a Holocaust film in which his protagonist Gilles, a Belgian Jew, poses as a Farsi speaker with an Iranian background in order to survive: luckily for him, the camp commandant wants to learn Farsi so he can go to Teheran and live with his brother.

The ludicrousness of the premise aside—Lina Wertmuller made a masterpiece out of a similar storyline with Seven Beauties, in which the survival-at-all-cost antihero had sex with the obese female commandant of a concentration camp to stay alive—Perelman and writer Ilya Tsofin’s creaky plotting militates against our complete sympathy, despite the very fine performances by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart as Gilles and Lars Eidinger as the commandant. There’s a first-rate Blu-ray transfer.

(Bayview)

One of those all-time inept “bad movies” along the lines of Plan Nine from Outer Space and Santa Claus Conquers the Martians, this 1953 grade-Z sci-fi flick by Phil Tucker has virtually little to recommend it—unless, of course, you’re one of those gluttons who seeks out and devours junk like this.

That’s, of course, what this 70th anniversary special edition is all about: not only do we get the amateurish B&W film in all its anti-glory in 2D and 3D versions, but there are also many contextual extras, including featurettes in both 2D and 3D and an entertaining commentary featuring the last surviving cast member, Greg Moffett.

(Lionsgate)

Another Nazi-fueled fantasy in which the underdogs have it all over the German monsters, Jalmari Helander’s relentlessly grim film never reaches the giddily masturbatory heights of Quentin Tarantino’s egregious Inglorious Basterds, where French and American civilians and soldiers murder Hitler.

Sisu and its “immortal” fighter, who has killed hundreds of Russians, takes on an entire Nazi squadron in the wilds of the Lapland region in occupied Finland with the help of truckful of women prisoners and finishes off the whole lot in spectacular fashion, is the epitome of a guilty pleasure, especially as played with single-minded viciousness by Jorma Tommila as the mainly silent title character. The hi-def transfer is excellent.

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up

Upcoming Events

No Calendar Events Found or Calendar not set to Public.