- Details

-

Parent Category: Film and the Arts

-

Category: Reviews

-

Published on Tuesday, 06 October 2015 23:23

-

Written by Kevin Filipski

Blu-rays of the Week

Beat the Devil

Salt of the Earth

(The Film Detective)

Two B&W classics have gotten the hi-def treatment, starting with John Huston's Beat the Devil, the great 1953 caper starring Humphrey Bogart, Gina Lollobrigida, Jennifer Jones and Robert Morley: Huston's sly directing and the top-notch cast give this black-comic adventure the extra push it needs to stay in the memory.

1954's Salt of the Earth, made by blacklisted members of the original "Hollywood Ten," is a crudely effective propagandistic drama about a miners’ strike against a heartless New Mexico company. Subtle it ain't, but its glimpse at workers' travails fifty years ago still resonates today. Both movies look decent if unspectacular on Blu-ray.

(Warner Brothers)

Though markedly inferior to the surprise 2012 original hit, that won't matter to anyone who just wants to watch this sequel to see Channing Tatum, Joe Manganiello, et al (excepting Matthew McConaughey), doing their patented stripper-dance moves. Steven Soderbergh's fingerprints are all over this, even if he's only listed as cinematographer and editor and his associate Gregory Jacobs is director.

For those who want cheesecake to go with their beefcake, there are too-short appearances by Amber Heard, Elizabeth Banks and Jada Pinkett Smith. The film looks sharp on Blu; extras comprise two featurettes and an extended dance scene.

(IFC)

Al Pacino gives what for him is an understated performance as a locksmith whose business and personal lives are fading in his twilight years as he juggles a distant Wall Street son, an aging and sickly cat, the memory of his dead wife and a budding relationship with a charming bank teller, played by the also usually flamboyant (but here low-key) Holly Hunter.

Director David Gordon Green directs with empathy, and his reining in both of his stars keeps this offbeat character study from becoming too off-key. The movie looks excellent on Blu.

Nowitzki—The Perfect Shot

(Magnolia)

This okay documentary about Dallas Mavericks' MVP Dirk Nowitzki—the first German-born player to make it truly big in the NBA—shows his life in Germany and eventual move to the United States and big league superstardom.

Director Sebastian Bernhardt not only talks to Dirk, his parents and mentor (who all speak German for those for whom reading subtitles may be an issue) but also his teammates, coach, GM, owner and even rivals like Kobe Bryant. The movie has a superior hi-def transfer; extras are deleted scenes and a Nowitzki interview.

(Fox)

When the young daughter of bemused dad and mom, after staring at the big-screen TV in their new house, says "They're here," why don’t her parents realize they’re in a remake of Tobe Hooper and Steven Spielberg’s 1982 ghostly smash?

Although it follows the original fairly closely—except for making the poltergeist-busting psychic male and including a lame fake ending—there’s nothing particularly interesting going on; the usually reliable Sam Rockwell and Rosemarie DeWitt are wasted as the parents. Watch (or re-watch) the original instead. There’s a first-rate hi-def transfer; extras are an extended cut and alternate ending.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show—40th Anniversary

(Fox)

It's been 40 years since the ultimate camp/cult movie was released, and if you're watching it for the first time, you might ask what all the fuss is about: the humor is sophomoric, the songs forgettable and the acting over the top.

But that's not the point: the movie has taken on a life of its own for millions of fans, and this new edition will make it even easier for them to party like it's 1975 whenever they want. The hi-def transfer is first-rate; extras include U.S. and U.K. versions of the film, audio commentary, deleted scenes, alternate opening and ending.

(Universal)

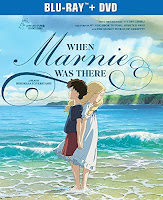

The latest animated masterpiece from the legendary Studio Ghibli is this moving adaptation of Joan G. Robinson's young adult novel about the memories of a young orphaned girl, who discovers her own family history while staying at a remote seaside village to recover from an illness. Unlike many Ghibli films, director Hiromasa Yonebayashi keeps the fantastical stuff to a minimum, but there remains the usual astonishing animation that explores the inner lives of its beautifully rendered characters.

The film (whose vibrant colors are vividly retained on Blu-ray) can be watched in the original Japanese or in English with familiar voices like Hailee Steinfeld, Vanessa Williams and Catherine O'Hara. Extras include featurettes.

(Alchemy)

A hot-shot lawyer’s fast-track to the district attorney's office is complicated by his obsession with paid escorts: once the escort service is busted by the feds, he finds his whole world—personal and professional—starts to crash around him.

For its first half, Mora Stephens' drama follows its protagonist’s double life with knowing plausibility: when it all becomes unhinged and turns risible, an accomplished cast—led by Patrick Wilson's lawyer, Lena Headey as his loyal wife and Dianna Agron as the escort he falls for—can’t overcome a script as obsessively one-track minded as its hero. The film looks decent on Blu; extras include deleted scenes with director's commentary.

Darling Lili

Oh! What a Lovely War

(Warner Archive)

Two massive 1969 box-office flops are back on DVD, starting with Darling Lili, Blake Edwards' overblown paean to wife Julie Andrews, who stars as the singer/spy: despite her charm, the entire enterprise is swamped by its large scale at the expense of the smaller, more interesting story that's been buried.

Likewise, Richard Attenborough's musical-comic look at World War I, Oh! What a Lovely War, favors big-name cameos from many British movie stars—John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson and Susannah York, for starters—and ends up with an incoherent, scattershot approach to its subject. Both films are, sadly, not restored; Lili extras comprise 19 deleted scenes, while War includes Attenborough's audio commentary and a three-part retrospective documentary.

(Film Movement)

The long, eventful life of Nathan Handwerker—who founded the Nathan's Famous hot-dog chain—is recounted by his grandson Lloyd Handwerker in this charming documentary portrait that presents the career and business sense (and, at times, lack of it) of the founder and his family.

Interviews with family members—including some who've since passed away—are interwoven with an audio interview with Nathan before he died for a warts and all glimpse at a successful family business buffeted by the winds of change. Extras comprise a director's commentary, deleted scenes and extra footage.

Fresh Off the Boat—Complete 1st Season

(Fox)

Reign—Complete 2nd Season

(Warner Brothers)

Fresh Off the Boat, from chef Eddie Huang's memoir, shows great promise in its 13-episode first season with its diverting premise of cultural clashes seen through the eyes of a precociously funny 12-year-old whose family has moved from Washington D.C.'s Chinatown to bustling Orlando in the 1990s.

In the second season of the entertaining historical drama Reign, young Mary Queen of Scots discovers, along with her new husband King Francis, that there are tough times ahead for France—where she lived before returning to the Scottish throne—starting with the Black Death and famine. Lone Fresh extra is a gag reel; Reign extras comprise deleted scenes and a featurette.

(Kino)

The proliferation of chemicals in our lives—from the products we use to the foods we eat and even the furniture we sit on—causes innumerable dangers to women's and children’s health and well-being, as Dana Nachman and Don Hardy's documentary shows.

This well thought out road map for how, against insurmountable odds like lobbyists and “bought” politicians, we can fix things contains damning circumstantial evidence and touching personal stories from several individuals. Extras are deleted scenes.