the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Film and the Arts

Art Review—“Beyond Monet” on Long Island

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Saturday, 16 December 2023 19:33

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Off-Broadway Play Review—Jen Silverman’s “Spain”

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Thursday, 14 December 2023 23:38

- Written by Kevin Filipski

.jpg) |

| Marin Ireland and Andrew Burnap in Jen Silverman's Spain |

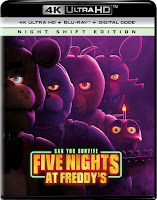

December '23 Digital Week II

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Thursday, 14 December 2023 03:53

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Retrospective for Daring Director Kijū Yoshida at Lincoln Center

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Tuesday, 12 December 2023 16:23

- Written by Jack Angstreich

Eighteen Who Cause a Storm

From December 1st through the 8th, Film at Lincoln Center—in collaboration with the Japan Foundation, New York—presented a long overdue retrospective programmed by Dan Sullivan—with all but two of the features shown in 35-millimeter prints—devoted to the work of the late Kijū Yoshida, one of the most talented Japanese directors to emerge in the 1960s; his political interests are a source of fascination but what the series revealed above all is his boldness and brilliance as a visual stylist, surpassing that of even some of his more famous contemporaries.

Yoshida studied French literature at the University of Tokyo and then entered the Shōchiku studio where he assisted Keisuke Kinoshita. He recounted his beginnings in Japanese film production in an interview with Pascal Bonitzer and Michel Delahaye published in the October 1970 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma:

After leaving university in 1955, I started immediately at Shochiku as an assistant director. At this time I wasn’t particularly set on making films, but as a literature student, I wasn’t happy with the stuffy academic milieu, and for this reason I left and turned to cinema. When I entered Shochiku, Oshima had already been there a year. For another five years, Oshima, myself, and the rest of the younger generation at the studio wrote scripts, and at the same time – outside the studio, of course – contributed to a journal, “Film Criticism,” of which Oshima was editor-in-chief. At this time Japanese cinema, above all that of the major studios, was a predominantly industrial, commercial cinema, against which we fought violently. By 1960 Japanese cinema was in crisis, mainly due to television. And it was because of this crisis that Shochiku decided to give the younger directors a chance. The first was Oshima, I was next. It was like that, almost by accident, that I was able to make my first feature, which I titled Rokudenashi (Good-for-Nothing).

A useful way of entry into appreciation and assessment of his cinema might be through the commentary of Noël Burch, one of the most important writers on Japanese cinema alongside such eminent Anglophone critics as David Bordwell and Robin Wood; in his entry on Nagisa Ōshima and the Japanese New Wave for Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, he said about Yoshida, “His early films, made for a major company, were quite traditional, intimist dramas, in the manner of [Yasujirō] Ozu and [Mikio] Naruse, but on a level with, say, post-war [Tomotaka] Tasaka (i.e., respectable).” Burch’s then commitment to a modernist aesthetic—he subsequently abandoned this perspective—may explain his considerable undervaluing here of the filmmaker’s early achievements.

Good-for-Nothing from 1960, a youth film and crime drama, is a remarkable debut, consistently visually dynamic if in accord with commercial norms. The Film at Lincoln Center program note provides this brief description:

Our protagonist is the Rimbaud-reading son of a prominent business executive; as he and his companions idle around, Yoshida visionarily renders their casual nihilism as an inevitable outcome of the sociocultural malaise resulting from Japan’s postwar reconstruction and subsequent economic boom.

The doomed, aimless run of the lead character at the movie’s end recalls that of Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds of 1958; Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, released the same year as Yoshida’s film, and Sam Fuller’s Underworld U.S.A., released the following year, have similar final sequences and Good-for-Nothing, along with the director’s other early features, like these classics and the early works of his Shōchiku contemporary Ōshima, is representative of what was an exciting new aesthetic sensibility in world cinema.

Even more impressive and original in style is his next feature, the corrosive Blood is Dry from 1960, one of the most extraordinary discoveries of the retrospective. Marcus Iwama’s summary of it in a review for Little White Lies is as follows:

The film begins when a salaryman named Takashi Kiguchi is laid off from his job; he then makes a dramatic, failed attempt at shooting himself in the head. A life insurance company gets wind of this story and decides to hire him as the mascot of their new ad campaign – literally selling suicide under the slogan: “It’s high time that you are all happy.” He reluctantly agrees, and after a staged photo reenactment, his image is plastered all throughout Tokyo. What follows is a narrative dance between a slimy paparazzo (Harada), Takashi’s ad agent (Ikuyo), and Takashi as they set out to exploit, control, and destroy one another.

The film in some respects has a satirical premise but the material ultimately becomes a vehicle for tragedy, invoking a harsh cynicism of the kind portrayed in movies like Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole from 1951 and Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success of 1957, but it has a more advanced, less classical, formal approach—exhilaratingly employing abundant use of handheld camera—and including a startling eroticism exemplary of the Japanese New Wave as well as penetrating insight into the psychology of fascism. Keiji Sada—a handsome actor that worked with Kinoshita, Ozu, and Masaki Kobayashi—is convincing as Takashi. Blood is Dry was screened in a glorious, black-and-white, 35-millimeter widescreen print from the Japan Foundation.

In the Cahiers interview, Yoshida outlined his early career thus:

When I reflect upon these last ten years, I tend to think in terms of three distinct periods. During the first, I made three features in a row, Rokudenashi, Chi wa kawaiteru (Blood is Dry), and Amai yoru no hate (Bitter End of a Sweet Night), all three circa 1960-61. And due to the fact that I had a certain degree of freedom, these three films shared a clearly political aspect. But from that moment, Shochiku began to consider us quite dangerous, and stopped allowing us to make our own projects. Oshima left Shochiku, and I spent a year there without being able to make a film.

Thinking back on it, if I had to define Japanese cinema prior to our generation – in other words, the cinema of Kurosawa and Kinoshita – I would say that these were films of postwar humanism. That is to say, in all of these films, man is obliged to approach another as his “fellow man,” and there was always an infinite faith in “mankind,” which was capable of anything. This was Japanese humanism – meaning that which was imported by the Americans. Meanwhile, around 1950 we had the Korean War, which forced the Japanese to realize that American democracy – or the Japanese democracy imported from America – wasn’t democracy at all. From that moment on, Japanese became aware of the need to think about everything in terms of man in such-and-such a situation. It is in this sense that, from 1955 on, Japanese in general – and we most of all – began to pursue a political stance that was antihumanist.

Yoshida’s very moving Akitsu Springs is one of his most beautiful films and was another revelation of the series, screened in an incredible 35-millimeter, color widescreen print. The project was initiated by Mariko Okada, a great—and indeed unutterably lovely—movie star, as a vehicle for herself to celebrate her one-hundredth motion picture. The actress, who had appeared in films by Ozu, Naruse and Kinoshita, requested Yoshida specifically, later married him and went on to star in all his films between 1965 and 1971. Tadao Sato, in his well-known collection,Currents in Japanese Cinema,presented this overview of the film’s story:

The hero of this film is a young intellectual who believes that Japan's defeat in World War II is actually a liberation, but he becomes a philistine and loses his ideals amid the turmoil and confusion of the immediate postwar era. In contrast, the heroine is a simple young girl who sincerely grieved over the defeat and now grieves over his loss of ideals. She continues to watch over him, until she loses all hope and commits suicide.

The film, while very visually striking and original, is more formally conservative than Blood is Dry—indeed, one might almost imagine it having been directed by Kinoshita; however, it obliquely suggested a new path for Yoshida that he was to explore in more radical ways in the second half of the 1960s. Akitsu Springs co-stars Hiroyuki Nagato, an actor who worked frequently with Shohei Imamura in the latter’s early phase. It also features a marvelous score by the esteemed composer, Hikaru Hayashi. In an interview with Chris Fujiwara from 2009, the director had this to say about it:

With Akitsu Springs (Akitsu onsen, 1962), the company was expecting a romance, a melodrama. And I too was thinking of trying to make a romance film. But romantic love is always betrayed by time, because it's only for a very short period of time that a man and a woman can think in unison. So for me a true romance film is a film that shows the gap between the woman and the man and shows that they go past each other without really finding a common meeting point.

Burch—in his influential 1979 book, To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema—remarked negatively on this work, stating that, “As early as 1962, in Akitsu Spa (Akitsu onsen), [Yoshida] had mastered a certain slick, post-war assimilation of Western style with a visual native veneer,” but auteurist appreciation of commercial cinema has allowed us to perceive the considerable merits of films like this, qualities often invisible to culturally mandarin viewers.

In the Cahiers interview, Yoshida reviews his subsequent departure from Shōchiku and its aftermath:

My “second period” began in the spring of 1962 with my fourth feature, Akitsu onsen (Akitsu Springs). This is a love story between a man and a woman taking place over seventeen years following the war. The success of this film allowed me to film Arashi o yobu juhachi-nin (Eighteen who cause a storm), where I showed young workers exploited by society and unable to organize: I wanted to prove that humanism has nothing to do with the plight of the working class. Shochiku withdrew it after four days. In my next film,Nihon dasshutsu(Escape from Japan), the last reel was supposed to show a young man going mad; Shochiku withdrew it from distribution in theaters. I knew at this moment that I could not in any way continue working for Shochiku.

Thus I left there in 1964. Thanks to a collaboration with a newspaper, I was able to make, independently of the five big studios, a film called Mizu de kakareta monogatari (A Story written with Water). In 1966 I started my own independent production company, Gendai Eiga Sha (Society of Contemporary Cinema). There I made Onna no mizuumi (Woman of the Lake), Joen (The Affair), Honô to onna (Flame and Women), Juhyo no yoromeki (Affair in the snow), and Saraba natsu no hikari (Farewell to the Summer Light). Despite being independently made, all these films were nonetheless distributed by the five big studios. In comparison to the earlier periods, now I had more freedom in choosing the subject matter for my films. For this reason I was able to hone in on the theme of man’s concrete situation, and specifically, I wanted to interrogate his subconscious. Thus, sex. It was in this way that I made Eros plus Massacre, the first film for which I did not secure a distributor in advance – in fact, I still have not found one in Japan. In exchange, I had the most complete freedom.

The quartet of films Yoshida directed beginning withThe Affairin 1967, seem closer in style and approach to the European art film, especially the work of Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni; the director spoke illuminatingly about these affinities in an interview with Alexander Jacoby and Rea Amit fo rMidnight Eye, published in 2010:

However, going back again to the original question, the two directors who had the biggest influence on me were Bergman and, indeed, Antonioni. It was quite a complicated influence at the beginning since at the background of the directors is strongly Christian, something I couldn't figure out when I first saw their films. Besides, in Bergman's films there is also a unique Scandinavian atmosphere that was impossible for me to fully understand, as an Asian, or as a Japanese.

Be that as it may, Christianity and other cultural aspects in their films are not merely a convention that is followed, but rather matters of an individual expression. For example, themes such as masculinity or womanhood, a portrayal of strong women who boldly endure hardship, through relationships with bad, and sometimes even violent, male partners - this was very appealing to me. This is something I specifically liked in Bergman. As for Antonioni, for him, a film was not merely a story. I know that not just from my own interpretation, but also because I met him personally, and when he was in Japan once we staged a public dialogue. I also wrote a short book about him, which was translated into Italian, and Antonioni himself, after reading it, wrote a commendation of the book that was published in an Italian magazine. After that, we became closer and met several times. Antonioni too completely rejects the notion of film as a story, for him what is most important is the "real image" of the human being, or existence, in Sartre's interpretation of the term. This was, as you know, very important for me too for a long time as the embodiment of true being. However, I don't like the movies Antonioni did outside of Italy, in America and so on. To be honest, I was quite disappointed by these films he made abroad.

Donald Richie provides thisprécisof the intriguing The Affair:

A young woman (played by the director’s wife, Okada Mariko) fights against her own sensual nature. She has her reasons, among which is this reaction against a mother who slept around. Nonetheless, when she gives in—with a young day laborer who had known her mother—she gives in thoroughly. The combination of well-to-do young lady and common laborer predicates society’s disapproval. Yet for the daughter, these meaningless social prejudices—violate them though she will—are the only “normality” to which she can cling.

The Affair has an exquisite jazz score by Sei Ikeno that was later re-used for Affair in the Snow (1968) and co-stars Isao Kimura—he had worked with Naruse and Kurosawa and appeared in other Yoshida films—in an effective performance and is memorably photographed in black-and-white widescreen as is the distinguished Flame and Women from 1967, which also features Kimura. Film at Lincoln Center offered this encapsulation of it:

Shingo (Isao Kimura) is unable to impregnate his wife Ritsuko (a brilliantly restrained Mariko Okada), so the couple turns to artificial insemination in order to have their child. The procedure is a success, but as time goes on, Ritsuko finds herself increasingly drawn toward the mystery man whose sperm allowed her to get pregnant.

In A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors, Jacoby offers a provocative statement on Yoshida’s politics in connection with this film:

Here as elsewhere, Yoshida’s attitude was implicitly conservative; the technological advance that allows a sterile man to have a son cannot overcome an instinctive belief in the importance of biological fatherhood. The clearest example of this conservatism was, ironically, Yoshida’s most formally radical film, Eros Plus Massacre (Erosu + gyakusatsu, 1970), which juxtaposed the Taisho-period story of the relationship between a famous anarchist and a radical feminist with an account of life among the liberated, politicized youth of 1970. Here, Yoshida explicitly argued that the achievement of liberation will not lead to happiness, and that attempts to reform society are likely to founder on the impossibility of changing human nature. It may be significant that his only film to deal directly with power politics,Martial Law(Kaigenrei,1973), was an account of a revolution that failed: the militarist uprising of February 26, 1936.

This ostensibly comports with Yoshida’s remarks on Oshima in the Midnight Eye interview:

This is another big difference between us, as I have never approved of his views about society and politics and his revolutionary desires, which he thought should take a violent form. Apparently he liked violence. That was a big reason for me to establish a distance from him.

The next two features that Yoshida directed are both magnificent and were among the most exciting discoveries in the retrospective. Film at Lincoln Center’s program note contained this summary of An Affair in the Snow, which was screened in an astonishing 35-millimeter print:

Yuriko (Mariko Okada) and a high school teacher, who’s also her lover, head out on vacation and arrive at a mountain resort, where Yuriko intends to end things between them. Circumstances lead her to contact an old boyfriend (Isao Kimura), and their reconnection heightens the emotional volatility of this already fraught trip.

This description was provided for Farewell to the Summer Light:

A fascinating transitional film for Yoshida,Farewell to the Summer Lightfinds the restless iconoclast heading to Europe to tell the tale of an on-again-off-again romance between Naoko, a married expat who specializes in import-export (Mariko Okada), and Makoto (Tadashi Yokouchi), a Japanese scholar who is searching for a cathedral that served as the architectural inspiration for a church built in Nagasaki by Portuguese missionaries. Naoko’s family was itself a victim of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki in 1945, and her burgeoning affair with Makoto is haunted by the memory of that historic atrocity, but also by the ravages of global capitalism, with Yoshida taking a Godard-like interest in the aesthetic textures of a landscape littered with billboards and other forms of advertisement.

The film’s incomparable color, location photography was on full display in the stunning 35-millimeter print that was shown.

Burch discloses the next development in Yoshida’s career here:

Then, in 1969, he produced the film that made his small reputation in Europe: Eros plus Gyakusatsu (Eros Plus Massacre). This three-and-a-half-hour chronicle deals with the life and death of a famous Japanese anarchist, strangled by the political police along with his wife and child early in this century. The film combines scenes of present-day Japan—an adolescent couple evoke the memory of the martyr along with their own personal and ideological problems—with re-enactments of scenes from the anarchist's life and his relationships with three different women; and it also involves radically unrealistic, theatrical scenes in which the brutal execution and other symbolically crucial moments are staged with great lyrical intensity. Characters move back and forth between the two historical periods (a woman in period dress takes a modern train, gets out at a modern station, ultimately reaches a period house), and the treatment shifts from semi-realism to extreme stylization, in particular through radical decentring of the (CinemaScope) frame and skilful use of telephoto lenses. The culminating fantasy sequence of the imagined death of the martyr, toppling screen after screen in headlong, lurching flight, is one of the most splendid variations I know on histrionic death, an age-old theme of Japanese culture.

Fred Camper’s capsule review of Eros Plus Massacre is also worth reproducing:

Said to be the most important work of the Japanese new wave, this beautiful and provocative 1969 feature by Yoshishige Yoshida intertwines two narratives for a dialectical examination of love and politics, the individual and society. One, set in the early 20th century, is based on the life of anarchist Sakae Osugi, who advocated free love as part of his philosophy of personal liberation; the other, set in the 60s, concerns a journalist who emulates Osugi with two lovers, one a voyeur. Yoshida uses a variety of devices to distance us from the action, including scenes staged as theater, incidents presented in several different ways, and characters from the past popping up in the present. Yet the film is held together by his sensitive use of black-and-white ‘Scope: filling space with water, cherry blossoms, or urban surfaces, he casts his characters adrift on the screen just as the editing floats them across time. The film implicitly rejects what the actual Osugi called the “conscious destruction of past cultural residue” in favor of a more nuanced understanding of human contradiction, and in their quest for freedom the protagonists are foiled by the social order and their inherent limitations, becoming alienated from each other and themselves.

Burch was relatively unsympathetic about the director’s next two features:

In subsequent films, Yoshida has tried to develop the various approaches which characterizedEros Plus Massacreand were so brilliantly combined in it. Unfortunately, Rengoku Eroica (Heroic Purgatory, 1970) seems to me little more than a brilliant exercise in editing decentred shots woven into a rather obscure politico-metaphysical discourse, while Kokuhaku Teki Jogu Ron (Confession, Theories, Actresses, 1971) is a stylistically rather flat attempt to build a vaguely Pirandellian edifice round the professional and personal problems of three film actresses. One senses, in all his recent films, that Yoshida is going through a serious crisis: it is impossible for him to go back to the safe ground he trod beforeEros Plus Massacre,yet this film seems to have set him on paths which he may not be equipped to negotiate. Generally speaking, I feel that the need experienced by these three directors to 'reactivate' the overt stylization to be found in classics such asA Page of Madnessor, closer at hand,RashomonandThrone of Blood,has overshot its mark, so to speak, falling into a mechanistic aestheticism.

These films were difficult to evaluate on a first viewing but I would reject the claim that Confessions Among Actresses is “stylistically rather flat.”

I look forward to seeing all these films again as well as the remainder of Yoshida’s works, which surely deserve much more exposure.

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up