the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Film and the Arts

September '23 Digital Week III

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 27 September 2023 22:38

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Early Short Films of the French New Wave

(Icarus)

This valuable two-disc set collects short films from French directors of the New Wave and surrounding names from the fertile 1950s, in which big shots like Godard, Truffaut, Chabrol and Varda are represented (including A Story of Water, a collaboration between Godard and Truffaut).

The highlights are two Alain Resnais classics—All the Memory in the World and Le Chant du Styrene, masterpieces in miniature—and a pair from Maurice Pialat, Love Exists and Janine. All 19 films have been restored and look magnificent on Blu, even though several (including the Resnais films) are available elsewhere on other releases, so your mileage may vary.

(Lionsgate)

In director Samuel Bodin’s eerie but clumsy debut feature, eight-year-old Peter doesn’t think his parents are what they seem and, after hearing the voice of someone behind his bedroom wall, he’s even more suspicious. The first half of this 90-minute movie is creepily effective but once Bodin and writer Chris Thomas Devlin decide to overload on obvious jump scares, it becomes impossibly risible.

Woody Norman is a properly intense Peter, but the gifted and usually impressive Lizzy Kaplan is hampered by a clichéd mom role that she can do nothing with. The film looks good on Blu; extras are three short making-of featurettes.

(Music Box)

In Emanuele Crialese’s precisely observed character study, Penelope Cruz plays Clara, a harried Spanish mother with three kids and a philandering husband in 1970s Rome who tries her best to deal with Adriana, her oldest child, who identifies as a boy named Andrea: Clara and her child, both outsiders, form an even closer bond, as does Andrea and Sara, a young Romani girl who’s also an outsider.

Although Crialese’s elaborate musical numbers that comment on the characters’ psychology are superfluous, he gets wonderful acting from the entire cast, especially the subtle portrayal of Andrea by Luana Guiliani. There’s an excellent hi-def transfer.

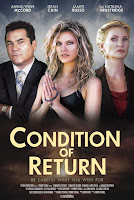

Condition of Return

(Stonecutter Media)

After Eve Sullivan shoots up a church during services, Dr. Donald Thomas interviews her to find out her motive—and her story makes up the bulk of this confused and gratuitous melodrama about how someone good can do something evil. Hint—it’s a deal with the devil.

Although AnnaLynne McCord persuasively plays Eve, she’s pitted against an unrecognizably bloated Dean Cain as Dr. Thomas (he phones in his performance) as well as director Tommy Stovall and writer John Spare, who cram so many unlikely contrivances and banal “ironic” twists into the plot that they must have come up with their own deal with the devil to get this made.

(Greenwich Entertainment)

Director Philip Carter’s fascinating documentary chronicles the last word in subterfuge from the CIA—with help from major misdirection in the form of a cover story from none other than reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes—as it raised a stricken Soviet nuclear sub from the ocean depths over a six-year period (1968-74), during the heart of the Cold War.

Through vintage footage and interviews with many of the principals—including the agency’s own David Sharp, prime mover behind the operation—this incisive portrait of a real-life government espionage also plays out like an urgent, nail-biting thriller—which, in some sense, it is.

(Film Forum)

Ulises De La Orden’s engrossing three-hour documentary exclusively comprises videotape footage of the trials in Argentina of the leaders of the military junta who spearheaded the “disappearing” of thousands of individuals considered enemies of the government from 1976 to 1983. Leftists and other democratic sympathizers were tortured and often murdered, and the men responsible for the coup and systematic annihilation of so many of their fellow countrymen are given the opportunity to defend themselves, unlike their victims.

Whittling down hundreds of hours of footage from the courtroom into three fascinating, enraging, often breathless hours, de la Orden allows those who were affected and survived to speak for both themselves and those who never returned. As the prosecutor says at the end of the trial, “Nunca Más” (never again).

(Film Movement)

The background of Fellini’s classic film La Dolce Vita comes alive through this engaging documentary portrait of one of its producers, Giuseppe Amato, who not only had to fight the director himself about its length, editing and premiere, but also the film’s distributor Angelo Rizzoli.

Director Giuseppe Pedersoli’s reenactments fall flat, as doc reenactments almost always do, but his interviews with key characters in the story, including Amato’s widow, colleagues and film historians, present a key glimpse into Italian cinema that’s worth watching.

(Gravitas Ventures)

Ashley Avis, who directed the 2020 Black Beauty remake, has made an urgent and timely documentary plea for the wild horses that roam across America’s western plains who are in danger of disappearing thanks to the government’s heavy-handed policies that are anything but humane.

Avis surreptitiously films the Bureau of Land Management’s barbaric culling episodes and unapologetically gets into the faces of the bureau’s spokespeople to discover what’s really going on. There’s a lot of justified anger and emotion underlining Avis’ stunningly photographed film, which shows the natural beauty of these majestic animals, who are shortsightedly under siege.

Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!

(Chandos)

It’s hard to believe that one of the great Broadway musicals, beloved and worshipped since its 1943 Broadway premiere and the classic 1955 film with Gordon MacRae as Curly and Shirley Jones as Laurey, has never before been heard in its entirety in a recording but that’s what this new release screams on the front cover: “world premiere complete recording.” In their first collaboration, Rodgers & Hammerstein outdid themselves with so many memorable and hummable songs, from the opening “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” to the climactic title tune.

The Sinfonia of London, led by conductor John Wilson, gives Richard Rodgers’ glorious score a high polish, while the cast—including a formidable chorus—sings Oscar Hammerstein’s lyrics beautifully. Best of all is Sierra Boggess, who may be the most pure-voiced Laurey that I’ve yet heard. This Super Audio CD has, unsurprisingly, wonderfully spacious sound.

September '23 Digital Week II

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 20 September 2023 01:23

- Written by Kevin Filipski

The Exorcist

(Warner Bros)

Still as shocking as it was 50 years ago, William Friedkin’s adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s crassly entertaining novel is a punch to the gut that works brilliantly, even after many viewings, because of its artful misdirection. You expect nasty shocks, but the slow build-up lulls you into believing you’re watching a docudrama about a young girl whose odd behavior eventually has no other explanation but the supernatural. When the horror arrives, it’s been grounded in such vivid reality that more is at stake than a simple “good vs. evil” battle: it’s personal.

This terrific 4K release contains the original—and still superior—version and the director’s cut, both looking splendid in UHD: Friedkin and cameraman Owen Roizman’s documentary-like touches accentuate the eeriness. And Friedkin’s expertly chosen music (Penderecki, Henze, Webern, “Tubular Bells”) sounds superb. Extras are commentaries by both Friedkin and Blatty as well as Friedkin’s introduction.

(Criterion Collection)

One of Orson Welles’ most dazzling visual achievements is his 1962 adaptation of Franz Kafka’s novel about everyman Josef K., who’s the unwitting target of the totalitarian regime that arrests and condemns him for an unnamed crime. Although the narrative at times gets sticky, the director is in his expressionist element, cinematographer Edmond Richard’s haunting B&W images complementing Welles’ off-kilter and off-putting camera angles, editing and music choices.

The main quibble is a rather stolid Anthony Perkins in the lead. Criterion’s release contains a superb UHD transfer, Welles expert Joseph McBride’s commentary, an archival interview with Richard and two with Welles: one with Jeanne Moreau (who’s in the film) and one at UCLA in 1981.

American—An Odyssey to 1947

(Gravitas Ventures)

Danny Wu’s documentary begins by taking a well-trodden path showing Orson Welles’ early life as a child prodigy through his first theater success and infamous War of the Worlds broadcast until it all falls apart following Citizen Kane and his Hollywood career dwindled to nothing after the abortive Magnificent Ambersons debacle. Wu then turns to two little known men: Japanese-American Howard Kakita (who survived the bombing of Hiroshima as a child) and Black serviceman Isaac Woodard (who was beaten so badly upon his return to the South after WWII that he was left permanently blinded).

Wu’s attempt to tie the stories of these disparate men together is often clumsy, for Welles’ artistic genius keeps getting in the way. (Even Welles’ discussion of Woodard is eloquent.) But Wu’s interviews with several talking heads—including Kakita himself—illuminate a necessarily expansive definition of the term “American.”

From the mischievous Australian sibling duo known as Soda Jerk, this lacerating critique of America during the Trump years is cleverly reedited from various repurposed scenes from dozens of unrelated films—including American Beauty, Wayne’s World, Robocop (which features the most pointed satire of today’s society), A Nightmare on Elm Street, Peggy Sue Got Married, etc.—which are tweaked to show how trump supporters and Hilary supporters acted during that fraught and, in hindsight, ridiculous and dangerous time.

The problem with the film is that it’s one-note: for all its humor and even insight, after about a half-hour, it starts to become redundant; we all know what happened—the reality was worse than any reedited bunch of film scenes and overdubs could make it—so why subject ourselves to it again?

(Magnolia)

The fascinating life of Bethann Hardison, who was one of the first Black supermodels and became an agent and, later, activist who paved the way for the stellar careers of such models as Iman, Naomi Campbell and Tyra Banks, is chronicled in this breezy but substantive documentary by directors Frédéric Tcheng and Hardison herself.

Hardison, of course, is refreshingly candid in nearly every sound bite and video clip over the decades; her son, actor Kadeem Hardison, Iman, Campbell, and Ralph Lauren, among others, speak touchingly and honestly about a trailblazer who became a lasting influence on the modeling profession for so many, whether they realize it or not.

(Kino Lorber)

Iconoclastic author Tom Wolfe—who coined such popular phrases as “the me decade,” “social X rays,” and “radical chic”—is remembered in Richard Dewey’s succinct but too brief (only 76 minutes!) documentary based on a Vanity Fair article by Michael Lewis, one of several admiring colleagues, associates, and family and friends who are interviewed about the author of The Right Stuff and The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Wolfe died at 88 in 2018, with his best work and cultural relevance behind him, but Dewey’s interviewees are sure his writing will endure; historian Niall Ferguson says it will be reevaluated and rediscovered by readers interested in what America was like in the last half the 20th century.

Don Pasquale

(Opus Arte)

One of Gaetano Donizetti’s delightful comic operas has been given a rollicking production by director Damiano Michieletto at London’s Royal Opera House in 2019; the humor is intact and the relationships are pointedly presented.

The great baritone Bryn Terfel makes a perfect Pasquale, and he is surrounded by a wonderfully capable cast that’s led by the winning Russian soprano Olga Peretyatko as love interest Norina. It’s all conducted with panache and verve by Evelino Pido, who leads the Royal Opera orchestra and chorus. There’s first-rate hi-def video and audio.

(C Major)

French composer Charles Gounod’s tragic opera follows Shakespeare’s classic play fairly closely after beginning with the coffins of the star-crossed lovers onstage—and Gounod’s enchanting melodies magnificently mirror Shakespeare’s poetry, especially in the lyrical scenes between the pair.

Russian soprano Aida Garifullina is a meltingly lovely Juliette and Albanian tenor Saimir Pirgu is a charming Roméo, with conductor Josep Pons leading a reliable reading of the music by the orchestra and chorus. Director Stephen Lawless’ 2018 Barcelona staging catches the sense of young romance and impending tragedy. The hi-def video and audio are enticing.

Succession—The Complete Series

(HBO/Warner Bros)

This compelling and hilarious series about ultrarich corporatists chugged along for four always watchable seasons, including the shocking but inevitable plot twist early in the final season that finally provided a real conclusion to what the title hinted at. The tension between a successful media corporation’s founder, Logan Roy, and his adult children, all of whom are in one way or another unworthy to succeed him—sons Kendall, Roman and Connor as well as daughter Shiv—reaches heights of tragicomedy worthy of Shakespeare.

The superb writing is complemented by the magisterial acting, from Brian Cox, who plays the Lear-like Logan, to Jeremy Strong (Kendall), Kieran Culkin (Roman), Sarah Snook (Shiv) and the scene-stealing J. Smith-Cameron as the family’s shrewd associate Gerri. All 39 episodes are included, along with several featurettes and interviews, but it's too bad that this addictive series (which was shot on film) has not been released on Blu-ray, let alone 4K.

Broadway Play Review—“The Shark Is Broken”

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 13 September 2023 02:01

- Written by Kevin Filipski

The Shark Is Broken

Written by Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon; directed by Guy Masterson

Performances through November 19, 2023

Golden Theatre, 252 West 45th Street, New York, NY

thesharkisbroken.com

.jpg) |

| Colin Donnell, Ian Shaw and Alex Brightman in The Shark Is Broken (photo: Matthew Murphy) |

Basically about three actors sitting around on a boat while their movie, Jaws, is taking longer than ever to make because the mechanical shark rarely works, The Shark Is Broken—written by Ian Shaw and Joseph Nixon—is a decent enough diversion.

Ian is the son of Robert Shaw, who famously played the monomaniacal shark hunter Quint in Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster 1975 movie, which was such an enormous hit that summer that Hollywood would never be the same after its astonishing success. So it’s no surprise that Ian plays his dad Robert in this curio about the frustrations of three actors—Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss, Shaw’s costars in the movie, are the others—as they sit around waiting for the green light to continue filming.

It's the barest of bare skeletons, which Shaw fils and cowriter Nixon are obviously aware of. In lieu of any real plot, the trio wiles away the boredom of waiting for the shark to be fixed by playing games, drinking, telling stories, drinking, singing songs, drinking, irritating each other—the bulk of the show is filler, but what the writers are after is the camaraderie, at first tentative but eventually hard-earned, of the actors, as diverse as can be. Robert Shaw was an infamously hard-drinking Irish-Brit; Roy Scheider was the city-dwelling everyman; and Richard Dreyfuss was, at least in this telling, a young actor with the biggest streak of insecurity in history.

A little of their back-and-forth goes a long way, so Shaw, Nixon and director Guy Masterson keep things moving by alternating longer, conversational scenes with shorter, atmospheric—and mainly dialogue-less—moments, which makes The Shark Is Broken marginally longer—it runs about 90 intermissionless minutes—but doesn’t provide much depth.

Amid all the wink-wink nudge-nudge jokes about how Jaws will be a flop (or at best a piece of junk that will make money but no one will remember in 50 years) or how Dreyfuss says he’s spoken to their director about his next movie, which will be about UFOs (incredulous, Shaw bellows, “What next, dinosaurs?”) or how President (not cowriter) Nixon—who, in real life, resigned while Jaws was being filmed—is the most immoral in history, the creators understand that The Shark Is Broken is about acting, and they have created juicy bits for each character, even if Masterson seems to encourage all three actors to go further into caricature than is needed.

Colin Donnell plays Roy Scheider with a pinched voice and exaggerated New Yawk accent, but he perfectly plays the moderating influence that the mostly calm Scheider must have been on the diametrically opposed personalities that were Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw.

Alex Brightman, always a physically adept comedian, plays Dreyfuss as a fidgety bundle of nerves—but since he’s a dead ringer for oceanographer Matt Hooper, the performance, funny and entertaining as it is, comes off as more of an impression of the character Hooper than the actor Dreyfuss.

From the moment he walks onto the stage, Ian Shaw is an uncanny doppelgänger of his father, and there are moments during The Shark Is Broken where it seems that a hologram of Shaw pere is interacting with the others. Ian also has the best lines as Robert reduces Richard to a pile of blubber with constant insults or when Robert extols the many virtues of being a drunkard—even while on the set, shooting.

But the coup de theatre comes at the climax when Ian recreates, word for word and gesture for gesture, Robert’s unforgettable Jaws monologue about the sinking of the USS Indianapolis after delivering the atomic bomb to Japan. Although it seems out of place, slapped on to the end of the play, Ian catches some of the nuances in his dad’s original tour de force and it’s a satisfying way to wrap up, as appreciative Jaws fans in the audience can attest.

Masterson directs snappily on Duncan Henderson’s precise recreation of Quint’s beat-up fishing boat, the Orca; Jon Clark’s lighting, Ninz Dunn’s projections and Adam Cork’s music and sound design coalesce to ground the enjoyably slight The Shark Is Broken in our collective movie memories.

September '23 Digital Week I

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 06 September 2023 22:26

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Mr. Jimmy ミスタージミー

(Abramorama)

Japanese guitarist Akio Sakurai —aka Mr. Jimmy—has pretty much turned his whole persona into a copy of Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page, from his guitars and musical tone to the costumes Page wore performing in concert.

Director Peter Michael Dowd introduces Mr. Jimmy as a serious musician who respects and loves the music he plays to the point where he makes it difficult for his bandmates in Zep tribute bands to perform to his exacting specifications. But Jimmy remains sympathetic throughout, offbeat but charming, with a real talent for music making—even if it’s someone else’s music.

(VMI Worldwide)

Do we need another documentary about recently deceased Queen Elizabeth II? Italian director Fabrizio Ferri thinks so, and he brings an artistic eye and subtle insight to this glimpse of her majesty through the eyes of the many photographers who were chosen to take official pictures of her over the decades.

There’s also fawning testimony from random people in pubs and parks along with the likes of Susan Sarandon, who contributes an amusing anecdote about meeting the queen. There’s even reverent narration by an onscreen Charles Dance, but the focus is rightly on the camera users, who discuss aspects of the queen’s “private” countenance even as they posed her for others’ consumption.

The Flash

(Warner Bros)

Andy Muschietti’s entry into the increasingly crowded superhero genre is a convoluted, occasionally fun but mostly enervating account of how the Flash deals with the murder of his beloved mother: he time-travels to meet his younger self and try and change past events by preventing her death—which then unleashes some unintended consequences.

Ezra Miller plays both Flashes, nicely modulated as the older but annoyingly herky-jerky as the younger; the great Spanish actress Maribel Verdu satisfies in a small role as his mom and Michael Keaton is slyly knowing as “alternative” Batman. But there’s too much clutter, both visual and narrative, to make this 144-minute slog consistently enjoyable. The film looks spectacular in 4K; extras are several featurettes, behind the scenes footage and deleted scenes.

The Complete Story of Film

(Music Box)

Irish filmmaker Mark Cousins does the seemingly impossible, creating a comprehensive history of the art of movies in a (relatively) brief 18-1/2 hours that is a treasure trove of information, witty commentary, brilliant use of film clips, location shots and interviews that make this a must-watch for anyone at all interested in the world’s most lucrative and widespread artistic medium.

Spread out over four discs are both of Cousins’ magnificent films on film: 2011's The Story of Film—An Odyssey and 2021's The Story of Film—A New Generation, the former divided into 18 chapters and the latter into two parts, covering eras from the silent and early talkies to the innovative filmmakers of Europe and Asia to Hollywood’s infamous blacklist and the digital transformation of the 21st century. Cousins finds engaging and provocative ways of tying several strands together thematically, historically, and artistically, although he’s not above criticism himself—his love for the technically proficient but shallow Baz Luhrmann, Christopher Nolan and Lars von Trier (for example) is, in my view, substantially misplaced. There’s first-rate hi-def video and audio.

Personal and Political—The Films of Natalia Almada

(Icarus)

Natalia Almada, a Mexican-American filmmaker, is rarely discussed outside of festival circles, but perhaps this illuminating five-disc set of several documentaries and one fiction feature will change that. For the past 20 years, she has been making singularly challenging documentaries, starting with her emotionally devastating 2011 short, All Water Has a Perfect Memory—about the drowning death of her sister at a young age—and continuing with To the Other Side (2005), El General (2009), The Night Watchman (2011), and Users (2021), the latter faltering a bit in bemoaning technology while using it to create stunning images.

Almada’s lone fiction feature, the observational Everything Else (2016), is also included, Almada makes personal films that are political (or vice versa), as the set’s title states, and her humanity and empathy shine through in all of her films. Brief featurettes and a three-minute director interview are the lone extras; too bad Almada doesn’t give more of her contextualizing voice to these often mesmerizing films.

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up

Upcoming Events

No Calendar Events Found or Calendar not set to Public.